Photos by Cassidy Lundgren

.

.

Everything was going according to plan. I had made it through law school, found a job that paid enough that I could pay for caregivers without government assistance, and found and married a beautiful redhead who happened to be my soul mate. We bought a house and got a dog. Next on the agenda: kids. That is where things went awry.

See Also: |

I had always heard having a spinal cord injury does not interfere with one’s ability to have kids, so I took it hard when my doctor officially declared I was shooting blanks. I had never really asked, “Why me?” when I broke my neck and became a quad many years ago, but for some reason finding out I was infertile shook me to my core. It is one thing to lose the ability to move your limbs; it is quite another to be stripped of your manhood — which is strangely how I felt about infertility. It took several rather awkward tests (I’m not one to enjoy an audience) to push me past denial. My wife overcame the loss much more quickly than I did, and eventually she pulled me through to the other side. We began to talk about adoption. I had no idea how little I knew about what that means.

Now, looking back after more than 10 years, and having talked with fellow crips who adopted children, I can say adoption is not out of reach for folks with disabilities. But for everyone — wheelchair or not — it is rarely a smooth ride. In many ways, adopting a child is like falling in love. It is exciting. It is frustrating. It is expensive. It can be a beautiful journey, or a trail to heartbreak. (And often you’ll find some of each.) The only thing for certain with adoption is that you will never be the same again. Our adoption journey changed the way I view parents of every type, and it proved that sometimes what you want is not as good as what you get.

Now, looking back after more than 10 years, and having talked with fellow crips who adopted children, I can say adoption is not out of reach for folks with disabilities. But for everyone — wheelchair or not — it is rarely a smooth ride. In many ways, adopting a child is like falling in love. It is exciting. It is frustrating. It is expensive. It can be a beautiful journey, or a trail to heartbreak. (And often you’ll find some of each.) The only thing for certain with adoption is that you will never be the same again. Our adoption journey changed the way I view parents of every type, and it proved that sometimes what you want is not as good as what you get.

Why Would Anyone Pick a Crip?

We decided we wanted to adopt an infant, perhaps because it is the closest to having a child the old-fashioned way. But we soon learned there are far more people hoping to adopt infants than there are healthy infants available for adoption. There are considerably more infants with complications or disabilities who are available to be placed for adoption, but we did not feel ready for that challenge. Honestly, I felt a little guilty, like I was falling into the trap of ableism by narrowing our search to “healthy” children.

We decided we wanted to adopt an infant, perhaps because it is the closest to having a child the old-fashioned way. But we soon learned there are far more people hoping to adopt infants than there are healthy infants available for adoption. There are considerably more infants with complications or disabilities who are available to be placed for adoption, but we did not feel ready for that challenge. Honestly, I felt a little guilty, like I was falling into the trap of ableism by narrowing our search to “healthy” children.

When we first went to visit the social worker at our adoption agency, I asked him pointedly about my biggest concern: “Can we realistically expect to adopt given the fact that I’m mostly paralyzed?” We had heard stories of quads being turned away by adoption agencies based on the assumption that a quad cannot be a parent. Really, why would anyone choose to place a child with us when there are plenty of nondisabled couples to choose from? The social worker stammered around a bit, finally saying he saw no reason why we should not be able to adopt. This wasn’t terribly comforting.

Then came the paperwork. Most people don’t have to do much to start a family. There are no laws that require a couple to become certified before conceiving a child. It is so easy that some people do it on accident! But if you can’t have a child the traditional way and want to grow your family through adoption, you have to prove you are fit to be a parent.

Each state varies some in requirements, but as a general rule, you must be ready to lay bare your life to the person conducting your “home study.” A background check just scratches the surface. We were asked to provide detailed information about our finances, parenting styles, relationship with each other, experience with adoption, medical history, and, yes, even our sex lives. They came to our house to make sure it was toddler-proof (even though we were adopting an infant), checked to make sure our dog was licensed, looked in the cupboards, interviewed us, and asked for character references. If everyone had to go through this process before having kids, overpopulation would not be an issue.

This hyper-invasive inquiry has a salutary purpose: to protect children from those who are not likely to be good parents. But it also creates opportunity for abuse. The information can be used to discriminate against or manipulate couples hoping to adopt. More on that later.

This hyper-invasive inquiry has a salutary purpose: to protect children from those who are not likely to be good parents. But it also creates opportunity for abuse. The information can be used to discriminate against or manipulate couples hoping to adopt. More on that later.

Along with the paperwork, we created a “profile,” a collage of photos mixed with a letter addressed “Dear Birth Mother,” introducing ourselves and explaining why we are hoping to adopt. Basically, the profile says in the subtlest terms why the expectant parents should choose to place their precious child with us rather than one of the other thousands of couples waiting to adopt a child. The first time we adopted, we obsessed over every word of the profile, trying to give a flavor for our lives and personalities. Despite the temptation, we did not downplay my disability or overemphasize it by jumping on the inspirational bandwagon. We played it straight, hoping someone might like us for who we are.

The way things are supposed to work from here, is that the agency would show our profile to parents considering placing a child for adoption. Eventually, an expectant mother would tentatively choose us, we would meet her, and if things went well, we would be considered “matched.” We would continue contact as we waited for the baby to be born, and shortly after the blessed day, the birth mom would sign away her parental rights to us. Up until that paperwork is signed, which by law cannot be before the birth or too soon afterward, the birth mother could change her mind about placement and the whole process starts over.

.

.

I’m not sure if our social worker was a poor communicator or if we were just overanxious, but soon we got into the ritual of calling once a week to see if anyone had looked at our profile. It was a very disappointing update. The agency had shown our profile several times, but no one had expressed the slightest interest. One day, when we called, we were told the social worker would be out of town for the next two weeks and no one would be handling our case in the interim. I was frustrated, but also, in a weird way, kind of relieved to put it aside for a while.

The Phone Call

Later that week, I was in an office building with a room full of attorneys, taking the deposition of a man who claimed to know nothing of consequence about anything important. In the middle of the questions, a woman came into the room and put a note in front of me. It said, “Call home immediately. (It is not bad news.)”

I took a break and called my wife. I told her, “Talk fast; my phone is almost dead.” Her response: “We need to go pick up our baby. They want us there before 5 p.m.” Huh? Baby? Boy or girl?

As it turns out, the birth parents had chosen our profile earlier that morning. The baby was just one day old when we picked her up from the agency — a tiny little bundle with a full head of dark hair. Nothing was official yet. We were to come back the next day to meet the birth parents and, if everything worked out, sign the initial paperwork.

We didn’t sleep at all that night. Nobody can sleep when there is a newborn in the house, but it was more than that. We had already fallen in love with that little girl, and the next day we were scheduled to meet the birth parents in what felt like the biggest job interview of a lifetime.

What if they didn’t like us in person?

I remember feeling very self-conscious about looking disabled as we were waiting to meet the birth parents. Then the birth father came in — a towering, athletic man with ocean blue eyes. He already had lines down his face from the tears. The birth mother and father had each written us a letter, which they handed to us as we introduced ourselves. Through tears, we read the letters, which described why they had chosen to place their baby with us. The strange part was we were so grateful that they had chosen us, and yet, they kept thanking us for providing their child the stability and opportunities that they could not provide for her at that time. Clearly, everyone in that room had the same motivation: to do whatever is best for that little girl who we all barely knew and already loved. Our worry that my disability might put off birth parents proved unfounded. In his letter to us, the birth father wrote they chose us in part because we had experienced the challenges of disability and would therefore be able to teach our child the value of persistence and compassion.

The next several months were pretty great, and at the same time, pretty rough. Because our little girl, who we named Olivia, has a few beautiful drops of Native American blood, we needed to get permission from her tribe and jump through various legal hoops. This all would have been simple enough if the attorney for the agency knew anything about how this process is supposed to work. Instead, I had to keep checking on what he was doing (or failing to do), all the while knowing the adoption could fall through at any moment if the birth parents changed their minds. We were whiplashed back and forth between enjoying our new baby and worrying that we might fail to cross some t’s or dot some i’s and as a result, lose our little girl. Finally, after eight months of worrying, nagging, and lawyering, we were able to go to court and finalized Olivia’s adoption. It happened to be the same day as our wedding anniversary.

Living Open Adoption

Early in the process of becoming certified to adopt, we were asked if we were willing to consider an “open adoption.” This, we soon learned, means that the adoptive parents remain in contact with the birth parents, and may even arrange to have the birth parents involved in the child’s life. When I first heard about open adoption, it sounded to me like a train wreck. Won’t our child be confused about who her parents are? What if after the adoption the birth mother changes her mind and goes Fatal Attraction on us? What if our child loves her birth parents more than us?

Despite these concerns, we agreed we would consider an open adoption in part because we thought it might increase our chances of being picked by an expectant mother. Now, after living 10 years of open adoption, I wouldn’t want it any other way. My fears about an open adoption were largely the result of my own insecurity about being a parent and common misapprehensions about birth parents.

When we first met the birth mother of our daughter, it was abundantly clear that she was acting solely out of concern for her baby. She was not trying to escape responsibility; quite to the contrary, she thoughtfully decided to sacrifice the joys of immediate motherhood in order to guarantee her child a better future. It was one of the most selfless acts of love by a mother I have ever encountered.

For us, open adoption has provided our children with clarity, not confusion. Olivia responded to learning that she was adopted the same way she responded to seeing that I use a wheelchair — without judgment or the slightest hint of shame. When Olivia was younger, she would run over to greet other people in wheelchairs (complete strangers!) as though they were family. When my wife asked her why I use wheelchair, my daughter responded without hesitation, “Some dads walk and some dads roll.”

.

Adoption was similarly unalarming for her. At first, Olivia assumed that everyone is adopted. One day she asked me who my sister’s birth mother is. When I answered, “Grandma,” she said, “No, her birth mother.” I had to explain several times before she was satisfied. Because Olivia developed a relationship with her birth mother at an early age, she never has to worry about where she came from or whether her birth mom loves her. She is showered with love by birth parents and birth-grandparents, as well as my wife’s family and mine.

Of course, not everyone has such a positive experience with open adoption. Some adoptive parents struggle to maintain healthy boundaries between their families and the birth parents of their kids. And some birth parents get frustrated because the adoptive parents are permitting too much or too little interaction with the adopted child, contrary to what was discussed before the adoption. Some of these problems can be avoided by careful planning prior to placement; but, as in all relationships, there’s bound to be miscommunications and struggles over boundaries. Adoption can be tough on all sides, but it is definitely worth the struggle.

The New Normal for Adoption

Four years after we adopted Olivia, we decided it was about time we found her a sibling. As we began the process for the second time, we were amazed how much had changed. The rise of open adoption, in combination with the omnipresence of social media and the internet, had changed the locus of power in adoptions.

Traditionally, adoption agencies have been the control center for adoption, collecting profiles and showing them to expectant parents who are thinking about placing. Today, agencies still play this role, but they are secondary to websites that charge hopeful adopters a monthly fee to publish their profile. These sites advertise to expectant parents and invite them to search the profiles to find the perfect home for their child.

Profile sites are just one tool for connecting with people who are thinking of placing a child for adoption. Domestic adoption is all about networking. You can troll adoption “situation” Facebook groups, create “hoping to adopt” business cards to give friends and pregnant strangers (not really), and create an adoption blog that builds on your profile.

While we were waiting to be matched with an expectant mother the second time around, my wife spent countless hours reading blogs written by birth moms, hoping to gain better insight into their emotions and expectations. This experience helped her feel more connected to birth moms, and the adoption community in general. Through reading about birth moms’ experiences — both good and bad — she felt better prepared to further develop her relationship with our daughter’s birth mom or any other expectant mothers who came our way. She also joined an adoption support group of fellow adoptive/hopeful adoptive moms. Sharing experiences with and supporting one another was invaluable to her in surviving the process. Think “free therapy.” Many of those women are now some of her closest friends.

Part of networking is learning how to talk adoption. We all know the words used to describe disability are laden with social assumptions and history. I cringe when an outsider talks about persons who are “wheelchair-bound” or — worse “invalid” — because such words imply a helplessness that I do not embrace. The language of adoption is similarly pregnant with subtle prejudices. For example, when someone says a mother “gave up” her child for adoption, it sounds like she got rid of something she didn’t want (like someone “gives up” smoking) or that the person shrunk from a challenge (as when one “gives up” fighting). It is better to say she “placed” the child for adoption. This suggests birth parents are not trying to escape responsibility, but rather trying to give their child greater opportunities in life.

One other rule on adoption language. Don’t ever ask an adopted child who her “real” parents are, unless you want to be slapped in the face by a very real, though perhaps not biologically related, parent who has labored for years raising the child. Trust me on this.

Resigning to Fate

As we ventured into the new normal of online adoption, my wife used the internet and various Facebook groups to learn about adoption laws in different states, which agencies were deemed more reputable than others, and which of those agencies seemed to have the most adoption situations advertised. Much of the information was helpful; some of it was horrifying. In Hitler-esque fashion, healthy, blonde, blue-eyed babies — especially girls — were attached to higher adoption fees. We also heard stories of agencies that lured expectant mothers from other states with promises of free rent and with the aim of circumventing birth father rights. And we heard of agencies failing to provide psychological support for expectant mothers, charging hopeful adoptive parents outrageous fees, and keeping the money if the expectant mother decided not to place her child for adoption.

You would think this information would have led us to carefully select an agency we could trust. But the truth is we never had a chance to choose. Once we found and connected with a particular set of expectant parents, we knew we had to play out the process to get our baby home. It may sound strange, but we knew when we first read the profile of a certain expectant mother that she would be the one to bring our child into the world. This was confirmed when she met us via Skype and revealed that she had the same impression.

.

Unfortunately, unbeknownst to the expectant mother, she was working with an agency that was particularly greedy, manipulative, and (we later learned) in constant violation of the law. Their fees were outrageously high, and their contract about as dirty as they come. (Have I mentioned that I’m an attorney?) Under their contract, which was not negotiable, we had to pay a quarter of my annual income up front and another lump sum in the same amount before the child was born. These fees were non-refundable, though the agency said if the adoption failed they would put the money toward another adoption, if we so happened to use them again. Every part of my legal, rational mind told me to run from the agreement, but deep within my heart, I knew it would work out.

That’s not to say, of course, that I never had second thoughts or concerns over the next few months. At one point, the expectant parents cut off contact with us, and we thought all was lost. The agency strategically kept us on a tight leash, withholding information and inserting themselves in the middle of every discussion with the expectant parents, even redacting emails.

Eventually, our son, Isaac, was born, and in due course, the adoption was finalized. Being born into an open adoption, Isaac gets the benefit of not only grandparents on each side, but also birth grandparents and birth aunts and uncles, and even birth great-grandparents. Basically, this means he gets lots of presents, so he likes it.

The Wheelchair Advantage

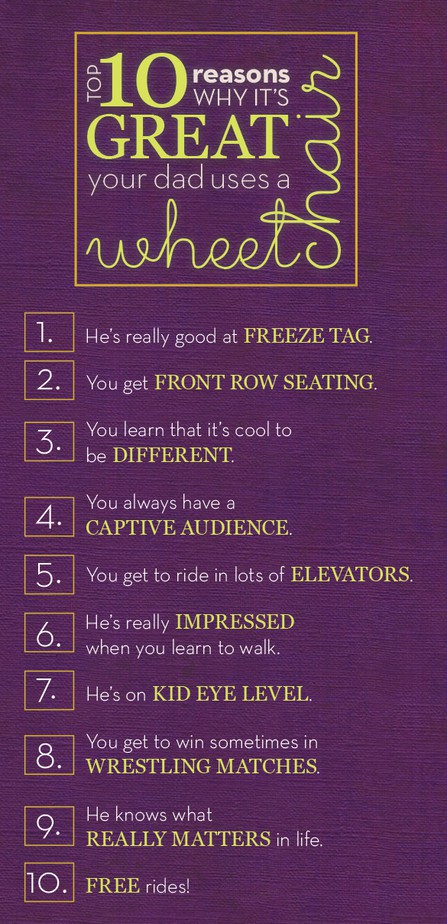

When we were looking to adopt the second time, we paid a specialist to give us advice on our profile and publish photo booklets with our story. It was worth every penny. After getting to know us, she recognized our profile completely left out an important element of our personalities — humor, especially what some might call “sick” humor. We revised the profile and included a box listing the top 10 reasons why it is great to have a dad in a wheelchair. This unabashed reference to the wheelchair, it turns out, was one of the deciding factors for the birth parents of our son. They had both grown up with a father who is disabled, and they knew something that I hoped was true but couldn’t know for sure: Sometimes, having a disability helps you to be a better parent.

When we first began our adoption journey, we were worried my disability would limit our ability to adopt. And it may very well be that we missed out on some adoption opportunities because of how others view disability. But when it came down to finding expectant parents who appreciated us for who we are, paralyzed limbs and all, it worked out perfectly. They chose to entrust us with what they held most precious, not despite my disability, but because of what it showed about us. As our kids grow up, I’m excited for them to learn about the courage, sacrifice, and love their birth parents demonstrated when faced with an excruciatingly difficult decision.

What Do Birth Mothers Say?

We talked with three birth mothers who placed a child in a family where at least one of the parents is disabled. Here is what they shared about their experience.

Q. Why did you decide to place your child with a family with a disabled parent? Were you looking for this attribute or did you just get lucky?

Alyssa: The bio didn’t place a lot of emphasis on the adoptive parent’s wheelchair, but rather on the accomplishments and desires of them as individuals and as a couple. What really solidified it for me was that the hopeful adoptive dad had gone on to do great things in the face of adversity. His wife very clearly loved him and his chair didn’t stop her from marrying him, and pursuing the life and family they wanted.

Coley: I wasn’t actively searching for a family with a disabled parent, but [the prospective adoptive mother] became the ideal choice for me because I knew she would raise our son to not see disability — and that would help him in having a relationship with my parented son, who has a disability.

Lindsey: When my boyfriend and I were looking for a family to place our son, the first thing on our list was not a parent in a wheelchair. But we found it so clever how the couple outlined the strengths of wheelchair users, that they made it look natural.

Q. There are a lot of profiles of parents hoping to adopt. What tips do you have for wheelchair-users who are trying to match with an expectant mother?

Alyssa: Include good photos. Also, make sure your bio mentions disability, but doesn’t focus on it, and that it highlights skill, experience, or passions that would make you a good parent — and be real. We’ll realize your wheelchair is normal and fine if that’s how you talk about it, right?

Coley: Don’t be afraid to talk about your disability. Be upfront and honest about what you can and cannot do. And don’t be offended at any questions an expectant mother may ask you.

From Fostering to Adoption

Kirstin Wansing and her husband Drew, a C4-5 quad, started off providing respite care for kids. After they got to know caseworkers and foster families, they decided to become licensed for foster care. To date, they have provided respite for 34 kids, emergency placement for three kids, and long-term placement for two kids. They recently adopted one of these children — an 11-month-old boy. She shares the following tips:

• Find a foster/adoptive support group. “This is a long, hard road and it doesn’t end the day the adoption is finalized,” she says, noting that the grief and loss of their biological family may affect some children forever.

• Be patient. “There is a lot of waiting and a lot of things are out of your hands and none of that is specific to disability,” she says. Even though her state does not discriminate against a prospective parent because of their disability status, she says the child’s needs must be met by at least one parent. “My husband can’t physically change diapers or lift our son, but I can. But there are also plenty of other things my husband can do and can do really well.”

• Accept help when it’s offered. “There are only so many hours in a day and I have to take care of myself, too,” she says. Also, she utilizes whatever resources are available to her and her family.

• Give yourself grace. “It’s OK if my house looks lived in rather than perfect or pristine. Oh, and coffee helps … lots of coffee.”

Adoption Resources

• AbleThrive, ablethrive.com. This website has articles on parenting from a wheelchair, including some adoption stories.

• American Academy of Adoption Attorneys, 317/407-8422; info@adoptionattorneys.org, adoptionattorneys.org. AAAA has a directory of over 400 adoption attorneys nationwide.

• AdoptMatch, 215/735-9988 or 800/TO-ADOPT; match.adopt.org. A service of the National Adoption Center, AdoptMatch allows you to search for adoption agencies, read reviews left by other families who have worked with the agency and correspond directly with the agency anonymously via the AdoptMatch website.

• Center for Adoption Support and Education, 301/476-8525; caseadopt@adoptionsupport.org; adoptionsupport.org. CASE provides research and access to mental health professionals who specialize in adoption issues.

• Child Welfare Information Gateway, 800/394-3366; childwelfare.gov/topics/adoption/. The Child Welfare Information Gateway has resources on all aspects of domestic and intercountry adoption, with a focus on adoption from the U.S. foster care system.

• Creating a Family, creatingafamily.org/adoption/comparison-country-charts/. Creating a Family tracks the requirements for adoption in various countries, so you can see which countries have “medical history” limits on parents hoping to adopt.

• National Council for Adoption, 703/299-6633; ncfa@adoptioncouncil.org, adoptioncouncil.org. The National Council for Adoption’s website has a wealth of information and links. Check out the “financial resources” tab, which provides links to adoption grants, loans, and fundraising sites.

International Options

Surprising as it may seem, people also have babies in other countries! Different countries have different rules for adoption, and they change often. So do your homework. Here are two international adoption stories.

Barb and Brett

When Barb, who is a para, and her husband decided on international adoption, they intentionally chose a country they knew would work with adoptive parents with disabilities without requiring both parents to travel. In 2003, China was that country. They had to provide extensive documentation, but the adoption went off without a hitch. When asked about how her daughter, who was 14 months old at placement, reacted to the wheelchair, Barb said, “I don’t recall her ever thinking twice about the chair. She seemed to instinctively know that she had to help me out by standing to get out of the crib and climbing up on my foot rests to get into my lap. She never ran away from me, and frankly, I think I’ve done too good of a job being independent. I think she still believes I should open the doors for her and not the other way around!”

Cheryl and Mick

What do you get when you cross a friend, a doctor, and nun? A very different route to international adoption. Cheryl and her husband, Mick, a C1-2 quad, decided to adopt a child from El Salvador. They did not use an agency. Instead, they used a series of personal connections to find their child. The outbreak of civil war slowed the process, but they were eventually matched with twin newborns. They were cleared to bring the children to the U.S. by the U.S. embassy. The Division of Family Services in El Salvador, however, recommended they not be allowed to adopt the children because of Mick’s disability. Cheryl and Mick appealed the decision, but were denied a second time. They appealed again, this time to the Supreme Court. In an unprecedented move, the judge did not follow the recommendation of the Division of Family Services and granted permission for the children to be adopted. The family later found out that the judge had had throat cancer and used an electronic device to communicate. This may explain his more enlightened perspective on disability.

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair