I have a brother in a remote land, but we’ve never met. Our ancestors sprang from different soils, but our hearts and personal histories are alike. A T4 para, he was injured on his younger brother’s birthday; my injury, at the T11 level, falls on the birthdate of my older brother. He rides a Mogo wheelchair made in southeast Australia; my TiSport was manufactured in the northwest United States.

Twice a week a nurse comes to visit Willie Gilbert in his modest home to care for a pressure ulcer on his ankle. I drive to a Portland hospital every two weeks to see my wound care nurse for my ankle ulcer. His aboriginal ancestors were exploited by European settlers who came to New South Wales in the 1800s. My European ancestors traveled west from New York state to California, in search of gold, about the same time. We are two sides of the same coin, as different as time, geography, ancestral roots, and culture will allow, yet we are united by something deeper.

Gilbert, 44, lives in Condobolin, a small town in the bush, a semi-arid red-soil land beset by drought for the past four years and, more recently, by a Canadian gold mining company with plans of digging an open-cut cyanide leach mine on the edge of Lake Cowal, a sacred site for Gilbert’s people. “Yeh, a lot of the old people used to live here in the early 1800s and that was their hunting grounds and their ceremonial grounds,” he says. “There’s sharpening tools, stones for sharpening spears, there’s spearheads, there’s carved trees and there’s probably burial grounds out there everywhere. This is sacred ground and we’ve been fighting it for the last two to three years, yeh. A whole group of us. There’s another group from this area that’s signed an agreement with Barrick Gold. We’re fighting their claim, because they didn’t have approval from their elders.”

To understand the aboriginal connection to the land, American readers need only consider their own history. “The aboriginal people and the American natives,” says Gilbert, “their traditions probably run along the same lines.” For both native peoples, an intimate connection with the physical environment is foremost. The aboriginal tradition begins with belief in dreamtime–“the time before time” when the spiritual world began to form. “The shape of the land–its mountains, rocks, riverbeds, and waterholes–and its unseen vibrations echo the events that brought that place into creation. Everything in the natural world is a symbolic footprint,” writes Robert Lawlor in Voices of the First Day: Awakening in the Aboriginal Dreamtime.

The Gilberts have descended from the Wiradjuri, the largest nation of aboriginal people in New South Wales. Does Willie feel connected with them? “Yeh, most definitely. That’s sort of ingrained in you from a very young age, through sitting and talking with your parents and grandparents about the land, and learning to respect the land and the animals–that’s what dreaming is all about.” Gilbert’s parents were of mixed ancestry. His grandmother and great grandmother are aboriginal, but his two great grandfathers were white. “So I’m not a full-blood aborigine,” he says, “but to be an aboriginal is not about the color of your skin, it’s what in your heart, and how you identify with the aboriginal community.”

In America, Gilbert might be mistaken for an Italian, with near-olive skin and straight black hair. But in Condobolin, his roots are well-known, not only because his uncle, Kevin Gilbert, was a respected poet and playwright whose works keep alive Wiradjuri history and traditions, but also because Willie, along with his brother, is one of five native residents who have a claim against Barrick Gold, the global giant whose ties to the land are best defined by what lies within it–in this case, an estimated reserve of 2.5 million ounces of gold.

Egg Power

Gilbert’s father was a rabbit trapper and a stick picker. When modern agriculture began to reshape the face of the land, low-paid rural workers were needed to clean up limbs from bulldozed trees–“stick picking.” “Growing up we moved around a bit with our parents,” says Gilbert, one of five children. “My father grew up on a mission. So did me mum.” A mission is an Australian version of an American reservation. There used to be two in and around Condobolin. Now there’s one. “They’ve changed the name to Willow Bend,” says Gilbert. “Most of these people are against the gold mine.”

The Lachlan River connects Condobolin with Lake Cowal, an ephemeral lake that is full seven out of every 10 years, the largest body of water in New South Wales, a major wetlands that is prone to flooding. Gilbert says there is danger of cyanide–6,000 tons a year by one estimate–leaching into the groundwater, a danger to the people of Condobolin and Wyalong and the surrounding area, and a threat to wildlife. At one time or another the lake is home to approximately 277 species of birds, many of them migratory, and the Lachlan is rich with perch and catfish. The sacred nature of the lake lives not only in its past history, but in the diverse wildlife that makes up its present character.

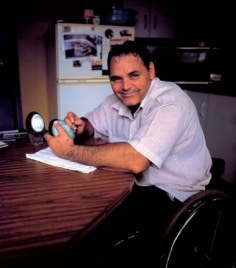

During emu egg-laying season, Gilbert hunts for eggs out in the bush. “If you know where to go and where to look, if you come across one or two nests, you could get at least 20 eggs,” he says. “The father does the incubating and raises the chicks. He will look after them until they’re about two years old. And he’ll just go around feeding them on berries and whatever they can find.” Gilbert’s interest in emu eggs has nothing to do with gathering food or raising emus. Besides protesting the desecration of the Wiradjuri heartland, he’s an artist, an emu egg carver.

An emu egg has a dark outer layer and gets progressively lighter as the artist carves down toward its center. “With mine I go into the white,” he says. “An emu egg has several different colors in it. A lot of the old fellows carve to bring out different shades of coloring, but I go as far down as I can and then I’ll bring out the white to highlight the picture more. The white is the last color. If you make a mistake when you’re down near the white, that’s it. You have to start all over again.”

Gilbert has been carving for only six years, but has carved and sold between 80-100 eggs. It usually takes three or four days for him to carve an egg. He works at home, at his kitchen table. “I can pull up and have a cup of tea whenever I want. It gets a little bit hard on the hands at times. I use a shears cutter, like they use in shearing sheep. They’ve got a hand piece, with two blades, one to comb and one to cut with. It’s got two blades and I use the smaller one for carving the eggs. Some of the eggs are a bit hard, and with the size of the egg and sitting in one spot for a long time, your fingers cramp up a little bit. That’s when you gotta take a break.”

He has carved images of an aboriginal man and woman, and a turtle in an aboriginal design, but Condobolin is not a tourist destination, not connected by any major road, so he has turned to more commercial designs. “Recently I’ve been doing the football emblems. You’ve got a football team and they’ve got an emblem. We’ve got the Sydney Roosters, and they’ve got an emblem with Sydney on it and a picture of a rooster’s head. They sell a little better than the other ones because a lot of people follow the football teams. The most I’ve ever gotten for one is $150.” Besides selling his carved eggs, Gilbert receives a monthly social security check.

Equivalence

One of Gilbert’s uncle’s best-known plays is The Cherry Pickers. It’s about migrant farm workers, mostly aboriginals. “The cherry pickers go into these communities and they all come together and live on these little farms and go about their working, and they’re times when they’re not working,” says Gilbert. The title and subject matter evoke Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, but when I mention the American classic, Gilbert seems unfamiliar with it. But I’d never heard of Kevin Gilbert, the aboriginal poet and playwright, either.

I grew up in California’s Central Valley, where Steinbeck’s novel was set, and where I had worked in the seasonal potato harvest as a kid. One summer, at 17, I joined a migrant crew following the potato harvest and traveled to eastern Washington to work for six weeks. “Oh, yeh,” says Gilbert. “We used to do that sort of thing when we were kids. That’s how we used to make our pocket money, our show money. We’d do seasonal work, picking prunes or tomatoes, picking peas, burr chipping.”

“Burr chipping?”

“Yeh, chipping burrs. Thistles. The tall plants with blue flowers and spiky leaves. To kill ’em out.”

Gilbert has been using a chair for 16 years, since 1989. “I was actually coming back from a football game from another small town with me brother and one of his mates. We got on the grog and had a few beers and coming home had an accident. Yeh.” In 1993, four years post-injury, Gilbert went to the University of Technology, Sydney, to concentrate on aboriginal studies. “If you don’t have a great knowledge of your history and the Australian history, it sort of happens that you’re always up to a lot of things that you’ve never known before,” he says.

He has four children, two sons and two daughters, but wasn’t married at the time of his injury. “Had a partner,” he explains. “That broke down not long after I had the accident. One [son] lives here and me youngest son lives in Canberra. I’ve raised him up since he was nine or ten. They’re both out on their own now. The youngest goes to college in Canberra and he comes home on the holidays. And I see me daughter every now and again.” I don’t ask about the missing child.

Things have changed since Gilbert’s father roamed the land picking sticks. “There’s more young people [of aboriginal descent] going through schools and going through universities,” he says. “People branching off and working in different parts of the community. People leaving Condo and going away for years, but they eventually come back.”

For now, Gilbert depends on his brother for transportation. “At the moment me car’s not going. I’ve got an old Valiant, made by Chrysler,” he says.

“Oh, yeah?” I say. “I once had a ’63 Valiant. Bought it with my seasonal potato money.” Comparing notes, I discover that he thinks the Valiant originated in Australia. “No,” I say, “America.”

Not long after, I ask: “The emu isn’t a marsupial, is it?”

“Naw. Naw,” he says. The phrase stupid question hangs in the awkward silence.

” So, what about accessibility?”

“In this community everything’s pretty much accessible. There’s only one or two shops that aren’t, for me. Oh, I’d like to go in, but they’re not accessible. But all government buildings in Australia have gotta have access for the wheelchair people, the people with disabilities. It hasn’t always been like this. Yeh, it has changed since I was first in a chair. Even the trains from Sydney are accessible. There are buses now that are accessible. Taxis. I could catch a train into Sydney but not from here. I’d have to go 100 k.”

“How far is Sydney?”

“About six hours.”

There’s a long pause. Our conversation is nearing its end.

“Some of the marsupials,” he says, “are kangaroos, wallabys, wombats, koalas, and there’s a whole range of little furry animals. … In Papua, New Guinea they have a tree kangaroo.”

“Can I buy one of your eggs?”

“Yeh, sure,” he says.

“Can you carve me something that says something about your roots?”

“Yeh. I can do the old black fella with the beard, the aboriginal man. They come out pretty good, them ones.” This reminds me of something he said earlier: “There’s people in this community that I’m not related to, but I’ll call them Auntie or Uncle. That’s sort of how it’s always been.”

Another pause. I don’t want to say goodbye. It may be a long time before I get to talk to my brother again.

“There’s one thing I want to tell you before you go,” he says. “Remember we were talking about the rugby league? Football? Well, we got a State of Origin league here, New South Wales vs. Queensland. Best out of three games. Queensland won the first one. New South Wales won the second. And the third’s going to be on the sixth of July, that’s next week. So if you’ve got a pay TV with a sports channel, you’d be able to watch that game.” “What time would it be on, your time?”

“It’d be up past 7 p.m. here.”

“That would be … about 2 a.m. my time. Maybe ESPN would have it on tape delay. I’ll look for it.” We’ve carved down to the white of the shell, to football–the universal language of men the world over.

” OK, then, mate, you take care.”

“You, too, mate. See you.”

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair

tuffy on NYDJ Launches Women’s Adaptive Jeans on QVC

Lisa Cooley on How to Fund an Expensive Adaptive Vehicle