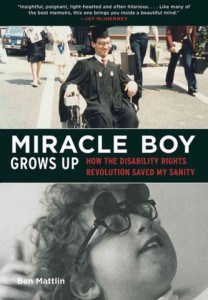

Book Review: Miracle Boy Grows Up: How the Disability Rights Revolution Saved My Sanity

January 1, 2013

Roxanne Furlong Miracle Boy Grows Up: How the Disability Rights Revolution Saved My Sanity.

Miracle Boy Grows Up: How the Disability Rights Revolution Saved My Sanity.

By Ben Mattlin. New York: Skyhorse

Publishing, 2012. 208 pp. (Available from Barnes and Noble and Amazon.com).

Reviewed by Roxanne Furlong

Toward the end of his book, Miracle Boy Grows Up: How the Disability Rights Revolution Saved My Sanity, author Ben Mattlin offers a quote from Ernest Hemingway: “Tell so much of the truth you can’t afford to have anything not true because it spoils the taste.”

Miracle Boy — so-named because his Aunt called him that — is quite delicious.

Mattlin was born with the rare degenerative condition, spinal muscular atrophy, a form of muscular dystrophy, robbing him of muscle strength. Growing up, his mother tells him he can do and be whatever he wants. She never allows too many tears or any pity, even once admonishing him after he falls out of his wheelchair because his father forgot to fasten the seatbelt: “Ultimately it’s your responsibility. You must always, always speak up. Understand?”

He was not quite 4 years old at the time, and will realize later in life that his mother’s conclusion about taking responsibility for himself is the basis of disability rights.

Mattlin is very young when he realizes that his life will be “split along two divergent paths — the normal expectations of a son of New York Jewish liberal educated intelligent parents to go out in the world, advance, and take charge of his own actions and fate, and the dangerous, ineluctable fragility of the hopelessly, severely disabled.”

Miracle Boy thoughtfully chronicles this revelation to be true as Mattlin struggles to live the life of a Harvard-educated writer who can barely feed himself, gets married and fathers two daughters but becomes desperately ill when the youngest brings home a cold from preschool.

Mattlin’s life coincides with the rise of the disability rights movement, of which he is oblivious until after college. He gives us a timeline of the movement, beginning with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 when he was 19 months old, adding that it never occurs to anyone — including his parents — that the law should extend to those with disabilities.

Thankfully not historically heavy-handed (we learn enough about the movement to research on our own), Miracle Boy details Mattlin’s life with just enough humor and pain — at one point explaining how he does not want his attendants to baby him, then wondering if he has created the attendant-cripple version of the Stockholm Syndrome when he allows one to be so rough with him while dressing that he has to rest at his desk before beginning work.

At 24, he moves to Los Angeles, meets a Jewish woman with SMA and becomes active in their local Independent Living Center. In Los Angeles, he meets activist and historian Paul Longmore, who explains to him the historical social construct of disability, inspiring the former MDA poster boy to write his well-received New York Times essay, “An Open Letter to Jerry Lewis.” He soon becomes senior editor of “One Step Ahead,” owned by Evan Kemp, the EEOC commissioner under President Reagan. At 25 years old, it’s Mattlin’s first official job with a regular paycheck.

But it doesn’t take long before Mattlin becomes disillusioned with the disability rights movement’s rigidity and moves away from activism. He starts freelance writing in the financial industry, where he is initially afraid to reveal his disability for fear of losing work, as does happen.

He respectfully spares us the cringe-worthy and personal details of his life that we can instead imagine. He does not, for example, go into too much detail when in his 40s he becomes sick with with ulcerative colitis that results in several months in ICU and nearly kills him. In fact, Mattlin’s timing is perfect, never over-analyzing or dwelling too long on any one subject or point.

A compelling writer, Mattlin describes his mission to lose his virginity at 20 in such a way that I had to read ahead to see if he stayed with the perfect companion he chose as his “victim.” And the way he tells the story of his thinning bones, I gasped aloud when he was prescribed Fosamax, now the subject of several lawsuits after allegedly causing femur fractures.

Often times poetic without being sentimental, Mattlin uses words like salmagundi when describing his wife’s emotional state while trying to get pregnant, then later, giddily exclaims that Gonadotropin, the hormone he has to take to increase sperm count, is made from the urine of postmenopausal nuns.

Miracle Boy is not a disadvantaged or angry young man’s lamentation; rather, a tasty morsel about a gifted writer and storyteller who can see the humor in the struggles of his fragile life, doing all it takes to stay alive and thrive while taking care of his family and advocating for the rights of those with disabilities.

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair