I fell asleep outside the other night. Kelly and I had been reading books with Ewan on the patio couch, and when Kelly piggybacked him off to bed, I flopped over and closed my eyes. I didn’t plan on going to sleep. But frogs were croaking in the pond at the bottom of the field, and a soft breeze was blowing in from the south. The next thing I knew hours had passed, and the stars were out.

We had gone outside to read because it was easy — just two pushes through the open garage door that separates our main living area from the outside patio. When I awoke, I slipped back inside just as easily. Coffee grounds spooned into the pot, teeth brushed, Kelly kissed, and I was back asleep in bed before my body had a chance to realize it was awake.

That night and a hundred other moments like it wouldn’t have been possible in the other houses I’ve lived in. Now I can keep an eye on Ewan and Lou chasing each other around the living room while Kelly and I are getting dinner ready in the kitchen. I can roll outside with a diaper bag in one hand and baby Lou on my lap. Our home is open, accessible and connected with the outside because that’s the way we designed it.

Other wheelchair users who’ve built their own accessible homes tell similar stories: a quad in the frozen north who can now venture outside in every season, a woman who can offer her wheelchair-using friends a fully accessible place to spend the night, a mother who can once again tuck her kids into bed, and a retired teacher who no longer has to risk a fall every time he goes to the bathroom.

It’s no hyperbole that building an accessible home can change your life. Here’s how five different wheelchair users across the U.S. and Canada got it done.

Land and Money

The first step in building a home is having a place to put it. Kelly and I were fortunate that my parents live on acreage. For our wedding present in 2015, they broke off a piece of their land for us. We were already homeowners since purchasing a condo in the wake of the 2009 housing market crash. We financed our build with profits from selling our Portland property and a loan of a little over $200,000. These funds, plus a lot of hard labor from us, family and friends, made possible a new 1,500-square-foot pole barn outfitted as a three-bed, two-bath home, right down the hill from my parents’ house.

Julie Sawchuk lived in a farmhouse on 10 acres in rural Ontario. She loved where she lived, but there wasn’t anything remotely accessible for sale or rent nearby. So, after a T4 spinal cord injury, she and her husband put in a ramp, did some minor renovations on the downstairs bathroom and moved their bedroom to the dining room. “But I still couldn’t tuck my kids in at night,” she says. They had a builder quote them $600,000 or more for a major renovation, “and we’d still have a 100-year-old farmhouse with a wet basement and a leaky roof.” Instead they decided to build a new home next to the old house, using funds from an insurance settlement Sawchuk received after her injury.

Michael DiBiasio, a schoolteacher with a T9 incomplete injury, was living in a two-level home with a broken stair lift too expensive for him to fix and bathrooms with 26-inch doorways too narrow for his wheelchair. “I used to transfer onto one of those rolling stools like they use in the doctor’s office,” he says. “Then I’d use the grab bars or the counter, pull myself in to jump onto the shower chair or use the toilet.” He made do for years because he had to. Then, a few miles up the road he noticed a condo development under construction. He stopped at the site and talked with the builder, who told DiBiasio he could build a unit however he wanted. After some haggling, they settled on a fixed price of $366,000 for an 1,800-square-foot unit modified to meet DiBiasio’s needs, a price the same or cheaper than similar-sized houses listed in the area.

Kary Wright, a C5 quad from Bashaw, Alberta, owned a farmhouse with his wife, Terry. Over the years they’d made it relatively accessible, but it wasn’t perfect. When the house burned down in a fire that Wright was lucky to escape with his life, he came away with a whole new perspective, a plot of land ready for a fresh start, and an insurance company willing to write checks for the rebuild.

Kimberly Chamberlain, a T4 para for 42 years, lived in a “standard, regular house” near Fresno, California, with a ramp but few other accessibility modifications. “You just get used to adapting,” she says. But after a while, she got tired of adapting. She had started a successful medical supply company and had the money to build a new home. She found a new development offering a selection of six different home styles to choose from and got lucky when the builder was enthusiastic about modifying a home design to make it accessible for her.

The Three-Legged Stool

Once Julie Sawchuk and her husband, Theo, had decided to build a new, accessible house next to their old farmhouse, an inevitable question arose: Where do we start? They began looking around for architects who had experience with accessible design. “There wasn’t a lot out there,” she says. “Nobody local, and there weren’t a lot of resources that I could find.”

Sawchuk did her own research, talking to friends and acquaintances of friends, making trips to visit anybody she could find who used a wheelchair and had a home. She learned so much that she eventually wrote a book, Build Your Space, about accessible home design, and became an accessibility consultant for commercial and residential projects. “We learned so much that I didn’t want other people to have to go through the same process of driving for two hours to go tour somebody else’s house,” she says.

In Sawchuk’s view, accessibility is a three-legged stool where the legs are safety, independence and dignity. “Anytime one of those three things is sacrificed, you have a lack of accessibility,” she says.

For people who are just starting to think about planning an accessible home, Sawchuk recommends you begin asking yourself where you’re expending more energy than you need to. Think through your whole day and you’d be surprised at how many examples you can come up with. “It could be having to roll up sidesaddle to your sink to brush your teeth versus being able to roll under, or having to reach too far over the sink versus not having to do that.” All these minor moments of extra effort add up.

Most people don’t have the budget to build a house or do a major renovation, but you can still start small. “Identify things that are easy, things that are low-cost, and you’ll have small wins,” she says. “You’ll realize the difference in energy expenditure, and then you get the motivation to do more and to problem-solve,” she says. “A $40 grab bar put in the exact right spot will help save your energy.” It’s typical to think about accessibility in terms of things you can do and things you can’t. But reframing it in terms of energy expenditure can help with motivation to tackle the small stuff.

The Bones

There are a few things that any truly accessible house needs to dispense with: Narrow doors, steps and thresholds all have to go. Thirty-six-inch-wide doorways for the main rooms are ideal, and for the front door, many retailers now offer 42-inch-wide options. The extra width can be helpful if you have a wide chair, or when you’re moving furniture. One thing to note is that the wider a door is, the farther you have to reach to close it. For a variety of adaptive closing systems, see the “Doors” products section.

Most wheelchair users rely on a single accessible entryway for their homes, but if you’re designing from the ground up, having stepless access at every door saves a ton of energy. You don’t have to go out and around to get to the other side of your house — you just go straight there. We paved our driveway and parking area and put in a concrete patio on two sides of the house, accessible from our main living area garage doors, with a concrete walkway connecting the patio and pavement. A hard-packed gravel garden area occupies the remaining space around the house, giving me 360-degree access to our house and outside area.

Slab foundations, made of concrete poured directly on the dirt, are not common for houses in the U.S. But they’re easy to pour and most construction crews have experience with them because many detached garages are built on slabs. A slab foundation is inexpensive and makes for a seamless and easy transition between inside and outside — otherwise you’re likely going to be trucking in dirt, which these days is no longer “dirt-cheap.” Another benefit is that you can put radiant heating in a slab, which is an energy-efficient way to keep the ambient temperature in your house comfortable. Plus, if you don’t mind the look of concrete, the slab can serve as your flooring. That’s what we chose, polishing and sealing our slab for around $5,000, which was thousands less than quality flooring would’ve cost. The concrete hides dirt and is easy to clean, and we don’t have a single threshold inside our house.

Concrete isn’t the only option for threshold-free flooring. Waterproof, click-together vinyl flooring is available to suit just about any style and can be laid anywhere, including kitchens and bathrooms. That’s what Wright, Sawchuk and DiBiasio all used in their houses. Chamberlain used a mix of flooring types, including hardwood in the living areas, stone in the kitchen and carpet in the bedroom, but planned so that transitions were all seamless. For people who want a natural look, modern engineered hardwood flooring can withstand moisture and even be used in bathrooms.

Working With an Architect

You might have a vision of architects working only on high-design, magazine-worthy homes. But the reality is that architects can provide some very practical services for anyone looking to build a home.

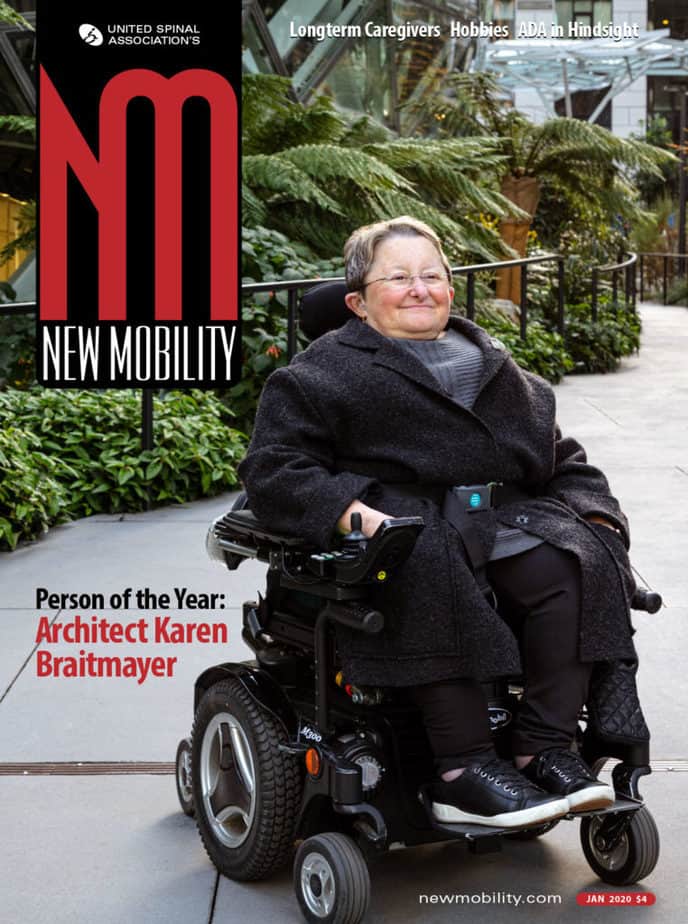

Karen Braitmayer, an award-winning architect and NM’s 2019 Person of the Year, says it isn’t always necessary to find an architect who’s an expert in accessibility code. “The ADA kind of hits the average,” she says. “But ‘average’ might not be the best fit for you and your family.” Accessibility consultants like Braitmayer, Sawchuk or others across the country can be helpful as a final set of eyes to check plans for issues that might affect your day-to-day life.

Most important for finding an architect, says Braitmayer, is finding someone you feel comfortable working with. “The architect/client relationship is very personal,” she says. “If you’re going to have someone designing your kitchen and your bathroom, you have to be upfront about what you need and how you use it.” When selecting an architect, you want someone who really listens to you and your needs and reflects that back in their design. “It’s great if someone designs stupendous, architecturally significant buildings … but if they’re not a good listener, you’re just going to get a piece of sculpture, not something you can really use.”

Braitmayer is using an architect for her own home build, a complex project that involves structural engineers, civil engineers, septic designers and landscape designers. “One of the primary jobs of an architect is to manage all the different players that have to come together.” She’ll rely on hers to “be my eyes and ears and really represent my interests when the project is under construction.”

Open It Up

When we began planning our house, we knew we wanted to keep it as simple as possible. One of the benefits of using a pole barn was the completely open interior, which meant that we could design our space however we wanted without having to worry about load-bearing walls. Layout choices were mostly about lifestyle. We had lived in a studio condo where there was no separation between kitchen and living room, and we had lived in old houses where the kitchen was off in its own room. We knew from experience that we liked the open concept.

Tangent alert: It’s not necessary to be a disability veteran or to have lived in a bunch of different places to start planning your dream home, but it certainly doesn’t hurt. I had lived in 12 different apartments or houses, 7 with Kelly, by the time we built our own home. All that moving gave me first-hand experience with what I liked and what I didn’t. If you’ve come by your disability by way of injury, DiBiasio recommends that you wait before taking the plunge and building a home. “Don’t do anything for the first year if you can avoid it. See what you get back (functionally). See what your individual needs are.” Everything is difficult when you’re new to disability life. See what stays difficult.

Back to layout: Open concept is functional for wheelchair users for obvious reasons. We need space to move, and open concept living makes the most efficient use of a given square footage because walls take up room, and hallways are wasted space. Fortunately, open concept living, dining and kitchen spaces are almost standard for new home builds in the U.S. these days.

Wright went to the local building supply store that his contractor worked with to find a standard home plan that they then modified to suit their needs. They moved a gas fireplace from the middle of the living room to a wall, expanded the main bedroom and bath, added a wraparound covered porch and an attached garage that Wright could put his office in. They also added extra glass. “We kind of went overboard with the windows,” he says, laughing. “We put the bedroom so that we could see straight south and west. All I do is hit the button and crank the bed up, and if it’s 5 in the morning and the sun’s coming up, I can look out and see deer walking around or geese flying.”

The kitchen is an area where individual needs reign more than in other rooms. If you do a lot of cooking, it makes sense to have lowered prep spaces and a roll-under stove top. But lowered counters aren’t always ideal for standers, especially those with bad backs. In our house, my wife does most of the cooking, and I do most of the dishes. She got the range she wanted, a 36-inch-wide gas industrial-style; and I got the sink I wanted, a big single basin, not too deep, that I can roll under.

DiBiasio’s only kitchen modification was to place their island 4 feet from the cabinets instead of the narrower aisle their plans originally called for. “We’ve got a pretty traditional division of labor here. My wife does most of the cooking and stuff in the kitchen, so we left it pretty much the way she wanted it,” he says.

Chamberlain cooks every day, so she lowered the counters to 34-inches, and set the height of her island, where her sink is, and the counter where her roll-under cooktop sits, another inch lower. She added a pot-filler next to her stove and a pull-out cutting board, as well as deep drawers to make accessing her pots and pans easier. A roll-in pantry gives her access to all the supplies that might normally be shoved to the backs of cabinets. “It makes it much easier not having to dig behind things to find what you want,” she says.

When you’re designing a kitchen, or any other space, Sawchuk recommends mocking it up in real life, even if that means chalk on your driveway. “Feel how much space that is between counters. If you have an island in the kitchen, is that enough space to turn around? Is it enough to get around the dishwasher when the dishwasher is open?” A mock-up turns a hard-to-visualize abstraction into a space you can move around in.

As for the sleeping and bathing side of the house, you’ll want your bedroom and bathroom to have more space than most standard plans allow, especially if you use a power wheelchair — yes, the disability tax extends to square footage. Wright added space to the main bed/bath and reduced the size of the other two bedrooms in their house, one now used as an office, and the other as a sleeping space for their daughter when she visits. If you use a ceiling lift, it’s worth considering a bed/bath design that gives a straight shot from bed into the bathroom.

Roll-in closets are great, but only if you have the space. Anything less than 6 feet wide feels tight once you get a dresser and a bunch of clothes hanging in there.

If you have the budget, it’s worth considering the accessibility of any spare bedrooms and bathrooms as well. Chamberlain put two bathrooms with roll-in showers in her home, so that when her wheelchair-using friends visit, they have an accessible bathroom too.

Outside In

Northern Alberta’s seasons are harsh, and Kary Wright loves being outdoors. Summers are short but hot, and the sun is intense; winters are long and cold, with a lot of snow and temperatures that regularly dip below zero degrees Fahrenheit. Sometimes Wright would tough it out during winter, but once he got cold, his day was done. To warm up, he says, “would take me two or three hours under a hot blanket.”

Wright wanted the new house to enhance his ability to spend time outside. The most important component of this was to add a covered porch that wraps around the entire house. The porch effectively serves as a buffer zone, a transition space between inside and out. The cover keeps out the high summer sun but lets it in during winter. “February we’ll get a hot sun on the front. It could be as low as zero Fahrenheit and yet it’s shirtsleeves weather on the deck,” he says. Plus, “nobody has to shovel.”

When Wright ventures beyond the deck in winter, he still gets quad cold. To combat the multihour warmup, he installed a portable hot tub in his bedroom. It’s a two-person SpaBerry unit that you can plug into a normal outlet. Wright has it set up in line with the ceiling-track lift system he uses to get in and out of bed. “Every evening it’s kind of our pattern that I get dropped in our hot tub and heated up, and then I sleep like a log,” he says.

In Fresno, the winters are mild but summers are blazing. Chamberlain put as much thought into her exterior space as she did the interior. Features include raised garden beds for produce and flowers, and installed awnings she can unfurl to combat the heat. Aisles are wide enough for her to pick, prune and water everything herself. Pro tip: If you garden, get expandable fabric garden hoses. “They’re a major effort-saver,” she says.

Then there’s Chamberlain’s lap pool, 40 feet long by 12 feet wide, partially set into the ground and with sides raised to a level allowing transfers from her manual wheelchair. The pool turns the brutal heat of August into something that Chamberlain can enjoy.

Where Kelly and I live in the Pacific Northwest, winters are usually mild, but summers can get quite hot. Insulation is nowhere near as sexy as a lap pool, but it’s the backbone of a system that keeps me happy to wander outside whatever the weather. To get the benefit of a tight thermal envelope without the specialized labor, we coated the walls and ceiling with three inches of spray foam insulation covered with mineral wool batts.

The insulation makes the house quick and efficient to heat or cool with a minisplit heat pump system. We leave the garage doors open — $40 magnetic screens keep the bugs out— until it’s 85 degrees because we know that we can cool the house right back down. In a poorly insulated house, we used to have to shut ourselves in, with windows closed and blinds drawn, whenever it got hot. I didn’t want to go outside because I knew that once I started to overheat, I wouldn’t be able to cool down again. Now, when Ewan wants to do some batting practice and it’s 95 degrees out? Sure, bud, you got 10 minutes — try not to line-drive me in the forehead.

Planning for the Future

It might seem odd for wheelchair users to need to think about future adaptations for aging in place, given that we’re already rolling. “None of us want to think about what to expect when we blow our shoulder … or have more needs than we currently do,” says Sawchuk. But function changes as we get older. A manual wheelchair user who lives into their golden years is likely to need a power wheelchair at some point.

When you’re planning your home, do yourself a favor and consider your future needs too. If you have good arm-strength now, think about how you would have to do things without that strength. Where would a ceiling lift go if you needed it? Could you make that turn in a power chair? Building for a less-functional future may cost more upfront, but it’s a lot cheaper than retrofitting down the line and a lot less heartbreaking than having to move because the space no longer works for you.

Another thing worth considering is future care needs. If you don’t have a personal attendant now, or have a family member assisting you with some daily tasks, how would it look when you or your significant other needs help? Could you make a self-contained guest area at one end of your home, or put in plumbing and electrical so that a space could easily be converted to an accessory dwelling unit in the future? You could rent out an accessory dwelling unit to help offset care costs or use it in a housing-for-care arrangement, helping to keep you in your home for the long haul.

The Reward

You may be getting an idea of just how big a project planning and building your own accessible home is. Let me assure you that it’s bigger than you can imagine. When we built our home, I understood that it was going to be like having a second full-time job, especially considering that Kelly and I were serving as de facto architects, project managers and grunt laborers all rolled into one. What’s impossible to plan for is how all-consuming the process is. You have to get comfortable spending more money than you ever have, over and over, making thousands of decisions, big and small, most of which you can’t take back. It’s high stakes, high pressure and all kinds of stressful. But once you get through it, man, is it worth it.

I didn’t talk to a single person who has built their own house and regretted it. Whether you like spending time outside, getting cozy with your family, hosting friends or having a calm place where you can decompress — living in a self-designed space lets you do whatever makes you happy, with a lot less effort. “It’s like the difference between pushing in sand and pushing on a hard surface,” says Chamberlain.

Sawchuk felt the same way. She remembers when they first moved into their new home. It was just before Christmas, and they were busy with the usual family hubbub and excitement of the season. Then January came along, and life mellowed out, but the Sawchuk’s typical postholiday energy slump never came. “I felt better than I’ve ever felt,” she says. “I realized all the energy I had been wasting in the old house, I now had for the things that I wanted to do.”

Resources

• Accessible Design and Construction — a virtual course from Julie Sawchuk

• Build Your Space book by Julie Sawchuck

• Gear Hacks — Hacking a Home

• Gear Hacks — Hacking a Home, Part II

• Gear Hacks — Hacking a Home, Part III

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Service-Connected disabled Veterans may be eligible for grants for building or remodeling an accessible home. The VA has pretty strict rules about accessibility for these homes, so best to work with your National Service Officer for the PVA or DAV.

I’m glad you made this point. I built a fully accessible house about five years ago and used my VA housing grant. If someone is considering using this they need to do their research. It is a one time use. The amount of money for building a house is considerably more than for remodeling. Something you should also consider is, when you build a house that is accessible, it doesn’t necessarily cost any more than building a normal house. Things like wider doors, doorhandles instead of door knobs, roll in shower, etc. If those are done as a remodel, they can be very expensive. Not only are you paying for the construction but also the deconstruction of the existing structure.

I wonder if there is help for people in wheelchairs to remodel homes? Grants, non-profits? It’s difficult to buy a home, and then have to remodel it on top of that to make it just basically functional. It costs A LOT of money. That is the reason to have to ”make do” instead.

I am confident the funding is out there. It’s not always easy to find. You might start by contacting a social worker at a spinal cord unit or rehab facility. If you are looking to build a house, the cost of building an accessible house doesn’t cost much more than just building any standard house. Even developers that build cookie-cutter houses in a new neighborhood allow you to specify certain options. That’s all you would be doing when you specified things like wider doors, roll-in showers, under sink, access, doorhandles instead of door knobs, etc..

https://vimeo.com/112705129

An accessible home becomes part of your being. 40 years ago, after buying a 3-story house, I knew it was a mistake. I swore the next one would be a rancher, which happened 22 years ago. The house cost $150k, and I spent another $100k widening doors, adding a garage wheelchair lift, and accessible bathroom, replacing the carpet with tile and hardwood floors and adding a door opener. Two years later, $23K more for an outside concrete wheelchair ramp with a switch back design and central garden feature (built to last). Stainless steel door kicks, corner reinforcements, door pulls, more shower bars and toilet supports were added as needed. For instance, shower bars were added after I broke my leg in the shower. You learn what was missed from accidents and setbacks. I got a chair lift two years ago and can now explore the basement. I put my first TiLite downstairs for roaming around. It’s a never-ending process. Next year I’m lowering the kitchen island and installing a sink and cook surface. Maybe a garden-to-deck wheelchair lift someday.