For Wheelchair Users, Finding Attendants Has Gone From Crisis to Catastrophe

May 1, 2023

John Beer

Photo by Jason Minick

Ken and JoAnn are facing a dire caregiving situation that may cause them to lose their home.

Susie Angel and Sandy White were a dynamic duo in Austin, Texas. Angel was an accomplished disability advocate, editor, organizer and dancer; White was her best friend and personal care aide who helped Angel and her life partner, Juan Munoz — both wheelchair users with cerebral palsy — stay healthy and active in their own home. “We had an awesome relationship,” Munoz says.

Then the unthinkable happened. One night in June 2022, White, 60, suffered a heart attack and died in her sleep. Though shaken by loss, Munoz, 52, immediately began caring for Angel, 53, by himself. He transferred her in and out of bed, helped with washing and dressing, made meals, managed medications, housekeeping, shopping and transport. “I could make it alone if I need to,” Munoz says. “Susie needed 24/7 service.”

Angel and Munoz began a frantic search for a new personal care aide. They could be hopeful, with an advantage over most, because Angel worked for years at the Coalition for Texans with Disabilities, an advocacy nonprofit with extensive ties in the area. CTD mobilized its full network of resources to find a PCA. But their hopes panned out to nothing. “We couldn’t find anyone,” says Dennis Borel, CTD’s executive director. “Forty-two different home health agencies … and not one had a single attendant that they could send to help our co-worker.”

As hard as Munoz tried, caring for Angel soon overwhelmed him. Reluctantly, he placed her in respite care for a two-week stay. “I didn’t want to put her in the nursing home, but I was exhausted,” he says. “She never came home after the nursing home.” Within a week she began choking on food and got a feeding tube, followed by three successive hospitalizations and pneumonia from which she never recovered. Angel passed away on Aug. 20, 73 days after White. “If we had an attendant, she would be here with us, I think, a couple more years,” Munoz says. “After losing Susie and Sandy … it was very hard.”

Borel acknowledges that his longtime colleague had complex health issues, including a doctor’s estimate in May that cancer could take Angel’s life in five years’ time and a lung tumor that proved too difficult to biopsy. But he is convinced that the lack of available home care hastened her death. “Even our organization, with all our connections, we couldn’t make it happen,” he says in a voice that still trembles with a mix of anger and grief. “What chance do other folks have?”

A nationwide shortage of PCAs threatens millions of disabled people and seniors who rely on services. These workers are essential to the right of disabled people to live in their own communities and avoid institutions. And while demand for their services grows, PCAs earn few if any benefits or chances for advancement, and most importantly, receive chronically low, uncompetitive pay. For workers, the pay is so poor that it often leads to poverty, burnout and quitting. For those relying on services, it is harder and harder to fill care-hours, stoking fears and uncertainty, health setbacks, or even loss of their homes or lives. Conversations with disabled people, workers, advocates and experts provide snapshots of a life-sustaining system under extreme stress.

Who Are the PCA’s?

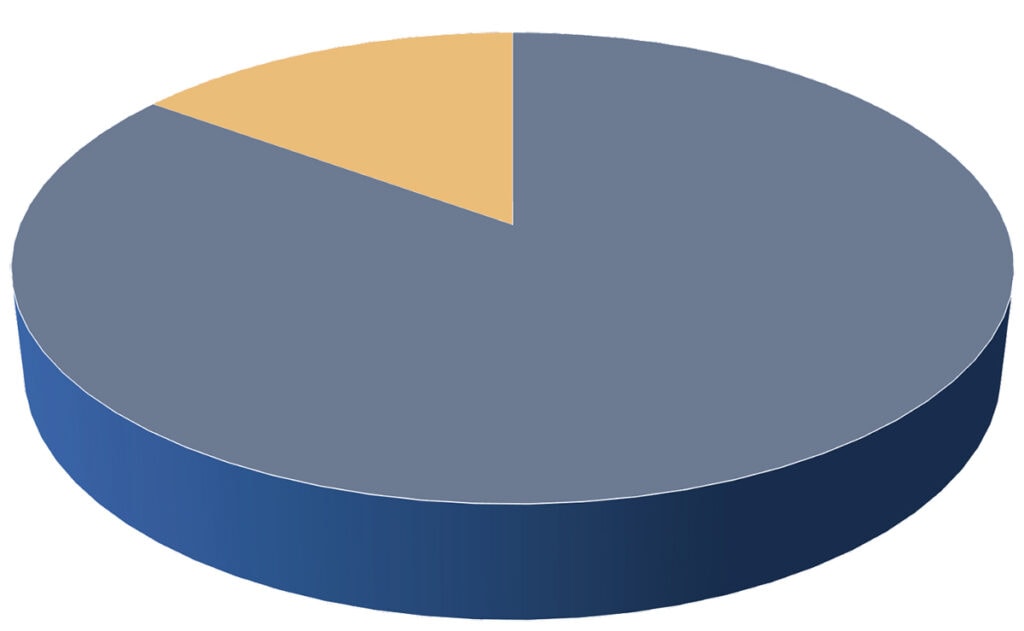

Women make up 85% of home care workers, including PCAs, home health aides and nursing assistants.

Median age is 48, with 36% being 55 and older.

People of color are 63% of PCAs, compared to 40% of the general labor force.

Immigrants make up 31%, compared to 16% of the general workforce.

Parents — nearly 30% of home care workers have at least one child under 18 at home.

Source: PHI

The Forgotten Workforce

Susie Angel was also prescient. Part of her advocacy work was to push for higher PCA pay. She invited reporters into her home to show how her well-being and productivity hinged on access to home-based services and on better pay for White and other care providers. Texas legislators have set the base wage paid by Medicaid to PCAs at $8.11 per hour. Though often boosted to a median of $10.82 by the agencies and providers who hire them, the pay for PCAs in Texas ranks among the lowest in the nation, according to the public-health policy organization PHI. “People are not willing to work for these wages anymore, and it’s been that way for a while,” Borel says. “Eight dollars and 11 cents is not competitive, and the workforce is evaporating.”

What’s happening in Texas is also happening across the country, as the wages of 2.6 million care workers are outpaced by other service jobs requiring less training. While Starbucks and Amazon average $17 and $19, respectively, plus health coverage, the average wage for PCAs and home health aides stands at $14.07 per hour, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nearly 19% of PCAs live below the poverty threshold, and more than half receive some form of public aid.

A longtime advocate summed up the situation succinctly: “Regardless of where you are, it’s more difficult to fill these caregiving jobs, because other jobs in the area are paying more that are much less emotionally taxing and that have opportunities for growth. It doesn’t matter if you’re in Portland or if you’re in central Illinois, the wages down the street are still going to be higher than whatever the home care wages are. The (home care) workforce crisis was in a crisis for decades before the pandemic. We’re at a point where it’s getting to catastrophic levels.”

It’s Very Hard to Find Help

Speaking on the phone on a late-January day, Ken and JoAnn (last names withheld) sound on edge. In the morning came news that President Joe Biden would declare an end to the COVID-19 public health emergency on May 11. To many it was only a passing item, but to Ken and JoAnn, the news meant they may lose a provision that helps keep Ken at home and a roof over their heads.

Ken, 62, and JoAnn, 64, are married and live in rural northeast Pennsylvania, 90 miles north of Philadelphia. JoAnn is a physical therapist with 40 years’ expertise, and Ken an energetic C5-6 incomplete quadriplegic who has worked and led an active life since his injury in 1979. Their lives changed in 2019 when Ken endured two heart attacks, a number of follow-up surgeries and procedures, and a long rehab. When he was discharged home after eight months, he relied on an array of medical devices: an oxygen concentrator, humidity condensers, nebulizer and more. For the first time, he needed home care.

A recent study by the city university of New York estimates that 17% of home care jobs are currently unfilled, and demand is growing.

Finding that care proved to be a problem. At one point they called 16 different agencies and turned up only one nurse — who didn’t show up. The first nurse who did arrive at their home worked until break time, and never came back. Ken felt “blessed” when they finally found a competent nurse. Then the pandemic hit and changed the landscape again. With school-aged children at home, the nurse had to quit. Since JoAnn’s work was in home health, she too was laid off. She learned how to take care of Ken, and after three months, had weaned him off the ventilator.

For a limited time, JoAnn was able to collect unemployment insurance. When they couldn’t find the home care workers they needed, she gave up her job entirely, sacrificing her salary and health care benefits so she could keep providing care. Ken also qualified for a few months of unemployment. Just as his unemployment benefits were running out, JoAnn was approved as his paid spousal caregiver under a pandemic-era emergency Medicaid waiver. They’ve somehow hopped from stone to stone, managing to survive, but now they’re looking for the next stone because the Medicaid waiver they’ve relied on will most likely end May 11. All along, they’ve been burning through their personal assets. “We’re in trouble of losing everything we worked for — our home, everything,” Ken says, “because the money ran out quick.”

With paid caregiving coming to an end, JoAnn wonders if she should return to work. “It’s going to be very difficult to find the help he needs,” she says. They can’t afford private nurses at $80 per hour, and besides, respiratory nurses won’t make house calls to so-called “low maintenance” patients like Ken who no longer use a ventilator. Ken chuckles. “It’s nice hearing I’m low maintenance,” he says before he takes an oxygen break.

In the meantime, their home mortgage has been in and out of forbearance, and they’ve had mixed results getting financial help to cover their winter utilities. Ken has written to their representatives at all levels of government, plus departments, agencies and caseworkers, trying to make something happen, and making sure they see there’s a dire situation now in home care.

From Really Stressful to Incredibly Frustrating

It was only after moving to Rochester, New York, in 2016 that Ericka Miller learned how home- and community-based services could make her life better. In Florida she had struggled with her health, but enrolling for home care services was difficult.

“Honestly, the best decision I ever made was signing up for it,” says Miller, who is 36 and has spina bifida. “It really changed what my life looked like for the better.” No longer did she have to struggle with cooking from her wheelchair in a galley kitchen, or with wheeling laundry to machines located outside of her two-bedroom apartment. Now she had reliable access to transportation to and from her full-time job.

But the pandemic exposed the fragility of her situation. She went from two PCAs down to one, and eventually, without a word, that one stopped showing up as well. For about three months, she had no one at all. She came down with what she suspects was undiagnosed COVID-19 and got so dizzy and weak she couldn’t transfer from bed to eat or go to the bathroom. “That was a really stressful few months,” she says. One of her friends, Wilfredo Rodriguez, traveled from Florida to help her as a temporary caregiver. Rodriguez, 35, ended up staying as her live-in PCA.

In February 2022, Miller’s fiancé, Parker Glick, moved in. Glick, 34, uses a chair due to arthrogryposis that limits his arm and leg movement, and needs assistance for several daily activities including transportation to get to his full-time job as a disability rights advocate. Rodriguez became the PCA for both of them, doing the work of two or three attendants.

Combined, Miller and Glick are allotted 77 weekly hours of attendant care, higher than the limit Rodriguez can work, so Glick says that he and Miller “gently undercut” the number of service-hours they need. But not claiming their full number of approved hours leads to a Catch-22: “If we do not get those covered by people, then the state can return and say, well, since you’re not using them, then … you don’t need them next year,” Glick says. “They don’t know that out of the kindness of our attendant’s heart, who also happens to be our friend, those hours are in fact being covered but they shouldn’t be.” It’s a situation that could be fixed by hiring a second PCA, which would give Rodriguez some time off, and give them a backup to avoid nightmares like what Miller went through before. But after nine months, they’re still looking.

At the moment, the household is in transition. Rodriguez has found a place of his own in town, 15 minutes away. It is good news and anxious news. Now all three will rely on the public transit system to get Rodriguez back and forth — and get Miller and Glick to their jobs. Transit timetables do not match up to the early morning hours the couple needs in order to get started on time, or with their need on weekends when transit service is limited. “It’s not really just like one thing we can point at, but it’s how all of these systems work together,” Miller says. “It’s incredibly frustrating.”

Our Followers Respond

We asked our Instagram followers to share your stories — good and bad — about how you’ve coped during the nationwide personal care attendant shortage. Here are a few of the responses, edited for length and clarity.

@resilient.apparel

My cousin, who was my primary PCA, gave me five months’ notice to ensure I had enough time to hire a new PCA. Sadly, it took almost nine months to secure full-time care. During those nine months, it was a painful, emotional roller coaster. I was lied to, had no-call no-shows, and was taken advantage of by seemingly high-potential caregivers that were “extremely interested,” who came to train, then flaked out. I can’t begin to count how many caregivers lied about being Covid positive instead of simply being honest that it’s not for them. Some ran off with money that I had fronted them. While I know no one would recommend fronting out-of-pocket money, you have limited choices when you are desperate to secure care. Considering the lengthy process of IHSS (California’s In-Home Supportive Services Program) enrollment, it was a gamble I had to take.

Where I looked: Care.com, Nextdoor app, IHSS jobs, Craigslist, ZipRecruiter and IHSS Registry. I posted flyers at colleges, on college job boards, and posted on various caregiver and IHSS pages on Facebook. I highly suggest doubling back if you don’t get a response. Sometimes the apps are glitchy or people simply overlook posts. I found most of my caregivers on the Nextdoor app and Care.com.

— Tammy, C4-5, California

@rycandoit

I am super thankful to have my family pick up my care hours, but the hours have put a strain on them emotionally and physically over the last few years. I am fortunate to be on a Medicaid program that allows me to hire whomever I want and pay a competitive rate, but even with that, I’ve been unable to find any caregivers. I’ve been searching to fill two open shifts since November 2022.

Thinking outside the box, I decided to try using job sites like Indeed and Monster. Since these sites won’t allow you to post an ad unless you are a business, I created a website (ryanicp.com) explaining my needs, shift openings and other job details. I made sure it looked professional and business-like, but I still got denied. Thankfully, Indeed approved me.

The first few times using Indeed I found great caregivers. I still have a few of them as of this writing, but I have not found a replacement for one who left months ago. I get applicants but they never respond, or they go through the interview process and agree to take the job then never show up for training day or just ghost me. I’ve tried other sites like care.com with similar results. My next step is to modify my home for a live-in caregiver. A live-in may be just as difficult to hire, but with me and my family at wits’ end, this seems like our best option.

— Ryan, muscular dystrophy, Oregon

@tigrislife

My son has been a C5-6 quad for almost three years now. He does qualify for IHSS and WPCS here in California, which is a big help, but it’s not enough to pay for knowledgeable and dependable caregivers. During the first year, he was blessed with two amazing caregivers who were nursing students. Unfortunately, they had to move on because they couldn’t afford to live in California. Eight out of 10 that have subsequently applied didn’t call back or didn’t show up for the interview. Applicants ask for more money during the interview, saying they would get it in a hospital or nursing home. When hired, two showed up for the shadow day and training days, then quit and asked me to pay them for their time. A few have argued or made excuses rather than listen, adjust and correct their work. They get too comfortable, don’t complete daily tasks, and lose focus on my son’s needs. We have found one woman, but she’s limited on the days she can work since she’s a student. I keep praying for the right people with the right skills to show up … and I continue to look for new avenues to find caregivers.

— Jamie Schaible & Anthony “Tony” Galvan-Schaible, C5-6, San Diego

@kevsullytalks

I’ve had to hire caregivers since I went to college at 18. When I started hiring them, it was full of trial and error, as I had never even had a job. Over the next five years, I gradually learned how to find the right people. I learned what to look for, how to manage them and create an effective working relationship. As an adult, I rely on local schools in my area to find caregivers by contacting nursing and other similar programs at these schools. I’ve built a personal database of caregivers around the U.S. to assist me on trips, as I also do motivational speaking on the side. This has been very effective in minimizing care disruptions.

— Kevin Sullivan, Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita, Buffalo Grove, Illinois

Join the conversation on Instagram at instagram.com/newmobilitymag

A Roulette Wheel of Attendants

Across the country in Sierra Madre, California, 13 miles northeast of Los Angeles, Lara Minges, 47, is a social worker and advocate at Hand in Hand, a multistate group organizing people like herself who hire PCAs or other home workers. Minges relies on round-the-clock availability of care due to dysautonomia and cerebral palsy. Her mother was her main attendant until she passed away from pancreatic cancer three years ago. What Minges found afterward was inadequate care and in one case even ill treatment from PCAs.

Luckily, her nephew was able to fly from New Hampshire to her aid. He signed up through the state’s in-home supportive services program to become her PCA and help her through the long process of healing a broken back. He wound up staying for 13 months, leaving in October 2022. “A lot of us just don’t have backup attendant care … and that’s dangerous, especially if we don’t have family, because family usually pitches in,” she says. “But if you don’t have other family … your option is you often end up in the hospital.”

Before her nephew departed, Minges enlisted the help of a friend and together they screened and/or interviewed 15 people for a suitable replacement. She also had to offer a substantial benefit: free room and board, which in Los Angeles County she estimates is worth $2,500-$3,400 per month. In her three-bedroom home, Minges houses her new PCA in one bedroom, and offers the third bedroom to a weekend PCA provided through the state’s Department of Developmental Services — a position that has been rotating between workers. Minges points out that most people who need services can’t offer a housing benefit like hers.

Six weeks in, she is “OK” with the new setup but still adjusting to the instability of rotating weekend attendants. She has had seven people in three weeks. High turnover is a job-quality indicator and a chronic problem among care workers in general. At times Minges feels vulnerable in her own home. She cannot transfer on her own or use Hoyer-type carrier lifts due to blood pressure issues. When a weekend PCA shows up who cannot transfer her accordingly, she is stuck in bed.

Review: Making Their Days Happen

Anyone trying to make sense of our nation’s byzantine approach to home health care and the complex realities underpinning the current caregiver shortage would be wise to pick up a copy of Dr. Lisa Iezzoni’s Making Their Days Happen: Paid Personal Assistance Services Supporting People with Disability Living in Their Homes and Community. Iezzoni, a professor of medicine at Harvard and a wheelchair user due to MS, has compiled a comprehensive overview of personal assistance services (her preferred term for in-home caregivers or PCAs) that covers how we got to the policies that govern PAS work today.

At the heart of Iezzoni’s work are over 40 interviews split between disabled individuals who rely on PAS and providers themselves. By mixing their candid first-hand accounts with data drawn from her research, she paints a detailed portrait that shows how essential these services are and how broken our approach to providing them is.

As someone who has relied on PAS for more than half my life, the anecdotes and insights from the interviews rang true but often didn’t shed new light on topics I tend to obsess over. Those drawn from the PAS providers were more interesting, but still more confirmative than thought provoking. That said, I have little doubt both would be eye opening and incredibly informative for people unfamiliar with this milieu.

Likewise, Iezzoni’s opening section on policies and social contexts provides a thorough look at the roots of institutionalization and the move toward in-home services over the last century. She relates the personal stories of friends and people she has met during her years of advocacy to hammer home the myriad benefits of in-home care and why it is such an essential option.

Through these personal stories, informative statistics and clear writing, Iezzoni comes about as close to portraying the totality of the PAS world as anyone can without experiencing it personally. She doesn’t offer any concrete solutions, but she does provide the knowledge and insights we need to share with the broader population if we are ever going to find any.

— Ian Ruder

A Silver Lining

As a disability rights attorney and person with a vision impairment himself, Thomas Earle has advocated and helped others to get home- and community-based services for three decades. He is chief executive officer of Liberty Resources Inc., the Philadelphia-area center for independent living, and his deep knowledge comes through as he describes a failing service system. But his voice is energetic, not despairing, because he knows a tide has turned. We would not be at this place, he says, without making major progress in turning around thinking on long-term care.

The home workers shortage “really is a problem that is the fruit of the past two decades of hard advocacy to convince the federal and state governments to spend more Medicaid dollars in community-based settings,” he says. “As that shift happened, … the demand for direct care workers in the community has grown significantly.” PHI tracks the trend: Every year since 2013, home-based services has made up a growing majority of Medicaid long-term care spending, while the share for institutions has trended down (see sidebar). Related to this, from 2008 to 2018, the number of PCA jobs jumped from about 900,000 to almost 2,260,000.

“We have not seen an equivalent shift necessarily in the wages, health care benefits, paid time off, overtime and pension contributions … for a very demanding job,” Earle says. “These are all common benefits of employment that American workers are accustomed to receiving. … Our federal and state governments have failed to catch up to what is necessary to make these jobs attractive to the workforce that’s needed.”

Biden’s Better Care Better Jobs Act would have invested a record $400 billion in stronger pay and supports for home care workers and users, but it failed to get through Congress. Now with a new Congress, activists will look for smaller bills that might gain bipartisan approval. A good example is the extension of the Money Follows the Person program through 2027, which was tacked onto the year-end $1.7 trillion Omnibus Spending Bill. MFP has helped 107,000 people in 43 states transition out of institutions and back into their communities.

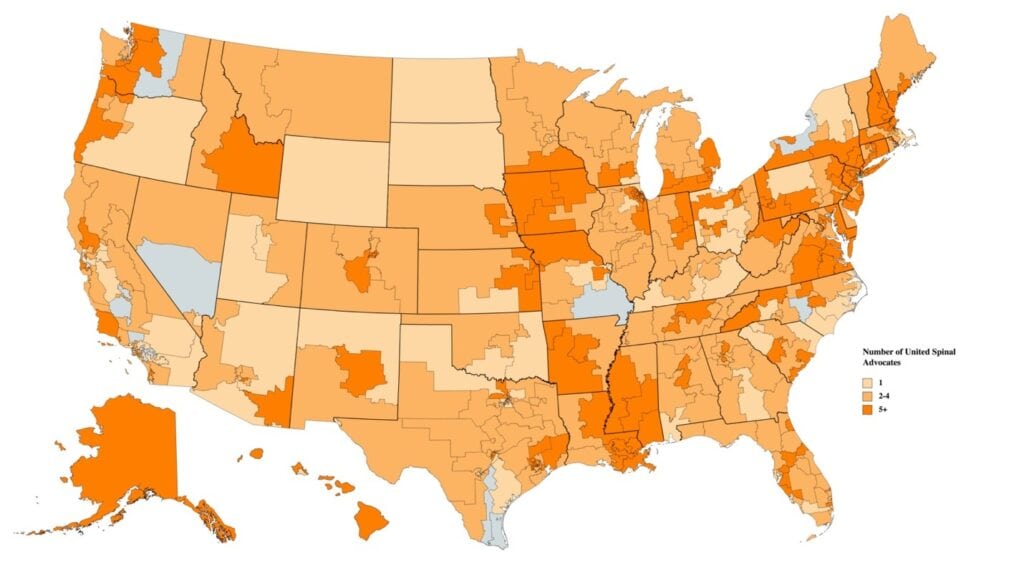

But with Congress divided, changes at the state level may be more promising. United Spinal Association’s new Care Support Working Group is prioritizing its efforts here (see ‘Fired Up’ below). “How we really want to utilize our working group the most is helping craft items for our chapters to pursue in their own states and in their own communities,” says Steve Lieberman, United Spinal’s director of advocacy and policy.

‘Fired up’: United Spinal Launches Care Advocacy Group

In the first meeting of United Spinal Association’s Care Support Working Group in January, members immediately identified care worker pay and job quality as key issues. “Our advocates all agree that we must take care of our care workers, and that we are failing in that — the minimal wage, the opportunity for professional advancement and training, but also allowing for those fast refills by spouses and other family members as their paid caregivers,” says Rebecca MacTaggart, United Spinal’s government relations coordinator.

Meeting monthly, the working group members are deciding on goals, shaped by the input and stories of United Spinal members. “We’re still open to new folks, new voices, new ideas,” says Steve Lieberman, director of advocacy and policy. “Nothing is set in stone.” Besides pay, benefits and training of PCAs, the group is looking at related topics, like creating information resources for those who suddenly need to find and afford PCA care or other home services like nurses or domestic workers; telehealth; and income tax and health insurance issues.

“We’ve got some very strong-minded folks involved, so I think we’ll do really well,” says Ken, who is featured in this article and also a working group member. But he encourages others to get involved in a pressing issue. “A lot of people don’t understand that they do have a voice. … By doing what we’re doing, I think it’s going to open a door for a lot of people.”

Other working groups have formed around issues that members feel strongest about, such as accessible parking, emergency preparedness and outdoor access. MacTaggart says, “It’s really amazing to see how fired up everybody gets.”

Members can add their voices in a number of ways: contacting representatives, action alerts, Advocacy Live online meetings, working groups, virtual advocacy days, the Roll on Capitol Hill, or working with chapters in state-based advocacy efforts.

To join the working group: unitedspinal.org/advocacy-program.

In New York State, thousands of “Fair Pay for Home Care” activists won a $3 raise over two years, and pay that will stay at least $3 above minimum wage. Now activists are pushing for their original goal of 150% of minimum wage, and a range of work benefits like flexible hours, better supervision, and a career ladder for advancement so it’s not a dead-end job. Likewise in Texas, CTD and other groups are pushing a newly convened legislature to hike wages, and peg those wages in some way to the cost of living. CTD says costs would be offset by a number of savings, like turning away from institutional care, which according to the state, costs 227% more than yearly home services.

Despite the popularity of home-based services among people with disabilities and seniors, governments continue funding institutions. “These are political decisions, and they are getting lobbied from industry,” Earle says. “Changing institutional care is like turning the Titanic. … We need to make policymakers understand.”

The needs going forward are dizzying. From 2020 to 2030, the total home care workforce, including home health aides and nursing assistants, will grow by almost 1 million new jobs, but they will have to fill 4.9 million openings due to workers leaving for other jobs or retiring. Likewise, the number of adults aged 65 and older is expected to nearly double from 49.2 million in 2016 to 94.7 million in 2060. In other words, the problem is not going away. In the future, the need will be even greater.

Resources

- Coalition of Texans with Disabilities, publisher of Crushing the Workforce 2.0,

- Hand in Hand, Domestic Employers Network

- Making Their Days Happen: Paid Personal Assistance Services Supporting People with Disability Living in Their Homes and Communities (see Review above)

- PHI, publisher of Caring for the Future

- United Spinal Association

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Excellent and comprehensive explanation of the problem. I could very easily be one of the stories if it weren’t for my incredibly supportive family. I posted this to Facebook!

This is not just wheel chair people. This is true for seniors with health issues, if you find an aide, they don’t stay long and all they want to do is be on their cell phones

The recruitment of persons assisting persons with a spinal cord injury is a global challenge. Everywhere the payment is below what is expected to be paid for the kind of assistance compared with other forms of similar work. It is probably one of the most challenging barriers to overcome in the future to ensure an independent life of persons with spinal cord injury. It has been an issue for many years but is now becoming more and more challenging because of the competition from other areas of the labour market where we can see an increasing demand for labour force. Other areas of employment are able to pay more per hour than those having a personal assistants scheme because of the spinal cord injury. If this barrier is not broken down then persons with spinal cord injury are becoming more and more disabled and their rights are becoming more and more challenged in violation of the United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities from 2006 (not ratified by the US but by almost all other countries across the globe), especially article 19 on inclusive living within the community. And since it is a global challenge we should somehow find a collaboration between organisations of persons with spinal cord injury to fight for elimination of this unjustified barrier which is enforced upon a group of citizens who are not able to perform daily duties without assistance from others.

My quad friend Denny lost his caregiver. He had trouble keeping them over the years. He ended up sleeping in his wheelchair because no caregiver could be found to help him transfer to bed at night. He eventually developed bed sores on his feet because of the constant pressure. They had to amputate his legs from the knee down! Then during his recovery his developed pneumonia as his body was so depleted and his passed away from it. All because he could not find a caregiver to transfer him to bed. A very preventable death in my opinion…

The hassle of Electronic Visit Verification (EVV) has made it worse for people with disabilities. EVV is a PITA I do not need.

Luckily, I live in a state where my wife is my paid caregiver. I’m a quadriplegic. Sadly, she makes more now than I did as a middle school teacher with a masters degree.