Taking on the Unfriendly Skies: Are Airlines Hearing Wheelchair Users’ Protests?

September 1, 2023

Kenny Salvini

Kelly Buckland faced a dilemma last December when planning a trip from his home in Washington, D.C., to his native Idaho. As a C4-5 quad, he could spend several days driving cross-country in his accessible van in the dead of winter, or he could book a one-stop flight with multiple transfers in and out of cramped, inaccessible planes, and get there in a day. “Every time I get on an airplane, I’m afraid,” he says. “I figure I’m gonna get hurt. I’m gonna get COVID. And my chair is gonna get broken.” For him, the choice was clear.

All wheelchair users face a similar predicament when deciding whether or not to fly. What makes Buckland’s story unique is that he is the disability advisor for Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg.

And so it went — the Department of Transportation’s highest-level disabled appointee loaded up his adapted van and drove from Washington to Boise and back, braving multiple road closures, delays and detours due to severe weather. “Altogether, I drove 6,000 miles, just to avoid flying on an airplane,” he says.

Like Buckland, I avoided flying for more than a decade after becoming a C3-4 quad, because of the horror stories I’d heard. When I finally did attempt braving the unfriendly skies, I had two power chairs destroyed by different carriers in less than a year. Forced into reluctant advocacy, I got to work. In a 2017 article in these pages, I chronicled the sad state of the airline industry, and I’ve spent the last six years working my way behind the curtains of the notoriously inaccessible industry.

In researching the 2017 article, I discovered a record of negligence spanning three decades and fed by a vacuum of accountability due to outdated legislation and a confusing, inefficient system for reporting damages. While there were glimmers of hope on the horizon, the overall picture wasn’t pretty.

Six years later, if possible, things seem even worse. Despite recent legislation and viral announcements claiming that a new age of air travel accessibility is on the horizon, the in-flight experience of wheelchair users worldwide remains largely unchanged. Even with the COVID-19 threat waning, more and more of us are, like Buckland, opting for road trips and/or smaller travel. To grasp why, I needed to understand the glacial pace of modern reforms and to plug myself into the loose network of like-minded advocates, influencers, engineers and policy wonks, who are focused on making the dream of truly accessible air travel a reality.

Empty Policies and Broken Chairs

Before the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked its havoc on the entire travel industry, there was a palpable sense that advocates were making progress toward more accessible air travel. In 2017, Sen. Tammy Baldwin introduced the Air Carrier Access Amendments Act, aiming to bridge the sizable gap between 1986’s Air Carrier Access Act and the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

The ADA’s crafters mostly left air travel out of the landmark civil rights legislation, under the assumption that the ACAA had the aviation industry covered. Their mistake became evident in retrospect. Unlike the ADA and most civil rights laws, the ACAA was not governed by the Department of Justice, nor did it include a private right of action — the ability to sue responsible parties for rights violations. Under the ACAA, our only recourse was to make a complaint to DOT through a confusing and convoluted reporting process that over the years led to infuriatingly little enforcement.

The Amendments Act called for a range of actionable accountability measures, such as mandating that all domestic carriers report data on mishandled wheelchairs stored in the aircraft cargo compartment. In its first congressional session, the Amendments Act failed to make it out of Senate committee but succeeded in invigorating conversation around accessible air travel.

Many provisions from the Amendments Act were included in 2018’s Federal Aviation Administration Reauthorization Act, including the establishment of an Advisory Committee on the Air Travel Needs of Passengers with Disabilities, and the drafting of an “Airline Passengers with Disabilities Bill of Rights” outlining the protections and rights afforded to people with disabilities in air travel. Despite the lofty title and 10 clearly stated rights, the exclusion of a private right of action made many advocates worry the bill had more bark than bite. “The bill of rights wasn’t going to do anything,” says WheelchairTravel.org writer and triple-amputee John Morris. “There were no new rights involved, and the key challenges that discourage people from flying were still in effect.”

The Reauthorization Act also required DOT to commission studies reviewing air-carrier training policies related to properly assisting passengers with disabilities, and determining the feasibility of in-cabin wheelchair restraint systems. The biggest headlines would come from the bill requiring DOT to finally start reporting the number of damaged wheelchairs and scooters by large domestic airlines.

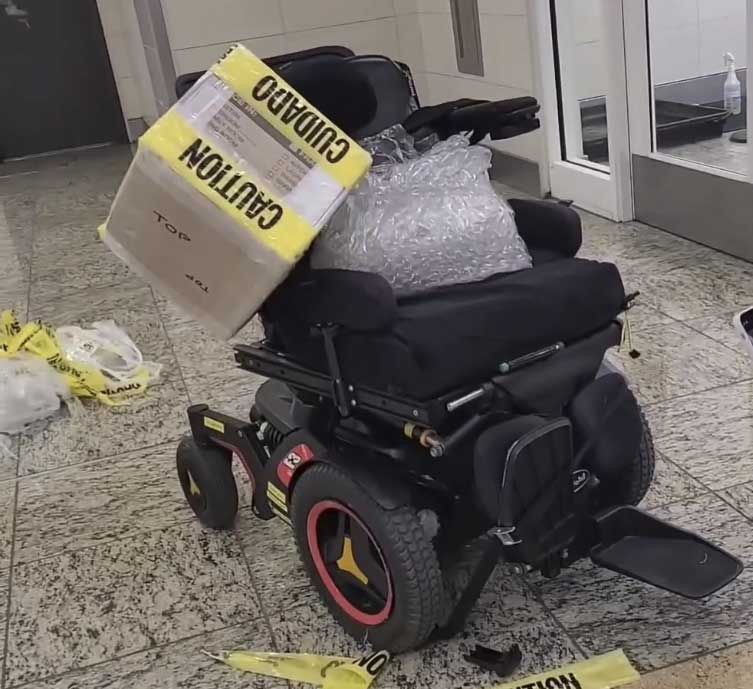

DOT released the first numbers in March 2019, and they were not pretty. By the end of the year, media outlets had latched onto the fact that airlines had damaged more than 10,500 mobility devices, a whopping 29 per day. The numbers predictably plummeted with the onset of the pandemic but gradually rose again and even exceeded pre-COVID-19 levels, with 11,389 chairs lost or damaged in 2022 — more than 32 per day.

All told, the airlines have misplaced, damaged or destroyed more than 36,000 devices from January 2019 to May 2023. Staggering numbers, but Buckland is not surprised. He sees it as a by-product of a system that has been getting consistently worse since he started flying 50 years ago. “At this point, I can’t even count how many of my chairs have been destroyed,” he says.

Considering the high likelihood of damaged equipment, it shouldn’t be surprising that so few wheelers are choosing to fly. Full-time wheelchair users account for more than 1% of the U.S. population, yet we represented less than 0.1% of the nearly 2 billion passengers enplaned by reporting carriers between 2019 and 2021. But the threat of broken chairs isn’t the only thing keeping us grounded.

Posting for Accountability

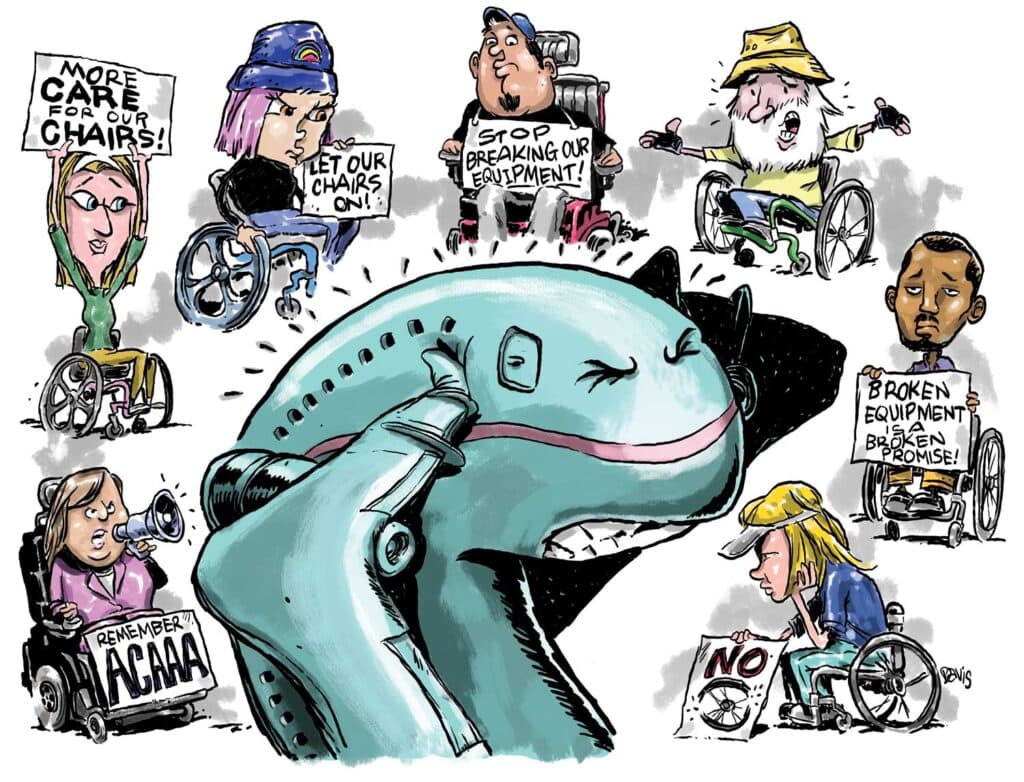

Disabled travelers are turning to the internet and social media to expose the negligence of the air travel industry and educate the general public and policy makers about the unequal treatment we regularly receive. Whether its videos of baggage handlers mishandling chairs, gate assistants dropping passengers and flight staff berating disabled passengers, or posts showing the extra lengths we go to for no guarantees, the accumulation of our stories is one of our best hopes for forcing the industry to change and make air travel more inclusive and equitable for everyone.

Ali Ingersoll @quirkyquad_ali

“TSA destroyed my chair despite my best efforts to build and create a very secure system. Back to the drawing board on creating the best design for transporting power wheelchairs during flight. Thankfully I think most of the damage is cosmetic and the wheelchair is still driving, but many of my friends are not this fortunate. I did have my manual folding chair with me, which many do not, so at least I had a backup option.”

Feranmi Okanlami @okanlami

“PSA: For all my wheelchair users out there, while flight attendants will often store their own luggage in these closets, the first priority is, in fact, your wheelchair.” Okanlami demonstrated how he broke down his wheelchair and put it in a designated closet for mobility devices on his recent flight to Washington, D.C.

Gabrielle “GG” deFiebre @ggdefiebre

“The flight attendant said ‘We don’t normally do this, but because it’s not crowded, we will.’ Then, on the flight back, I encountered similar resistance: ‘Chairs are supposed to go underneath the plane, not the cabin,’ ‘We have to see if the plane has a closet and if it does, if the first class passengers want to use it, then you can’t.’”

Kelly Narowski @kellynarowskispeaks

“I recently took an international trip, and since I was traveling solo, it was even more imperative that the airline not lose my chair or leave it on the tarmac. So, I exercised my right, mandated by the Air Carrier Access Act of ‘86, to store my chair in the cabin on all four flight segments. On the fourth flight, my chair didn’t fit in the cabin’s closet and I asked to find another solution. Surprisingly, the frame of my chair fit in the overhead! Having taken hundreds of flights, that had never happened before. It was a Delta 737.”

Karah Behrend @kindofaquad

“Huge thanks to @americanair for letting me try out the scooter on today’s flight instead of using the aisle chair. Not everyone knows this or needs to know this, but as a survivor of military sexual trauma, having strangers touching me to board me for a flight using the aisle chair is usually the absolute worst part of traveling. This all ends today. I’m taking back my right to travel with dignity.”

Cory Lee @curbfreecorylee

“I’m currently on a layover in Paris and flying to Cairo, Egypt, tonight. [The airport] staff has refused to bring me my personal wheelchair for this six hour layover, so I’m stuck in a manual airport wheelchair and have zero independence, can’t recline to alleviate pressure, and there are no seatbelts on this chair. Also, I just found out that @delta/@airfrance forgot to load my shower & commode chair in Atlanta, so I won’t have it for at least my first 24 hours in Egypt. No idea how I’ll use the restroom without it. This is ridiculous and exactly why we need better accessibility on flights!”

Sophie Morgan @sophlmorg

On the heels of launching her “Right on Flights” campaign to make airline travel more accessible for disabled travelers in the UK, Sophie Morgan posted a video documenting how she boards an airplane. It shows her transferring from her wheelchair to the aisle chair and workers strapping her into the chair before taking her to seat. “For people like me, this is how we board an aircraft. It’s not easy but it’s doable. Please don’t let the bad news stories about flying put you off. If you are ABLE to fly, FLY. The reward is worth the risk. Things MAY get broken but they MAY NOT. We can only hope for the best and plan for the worst, I guess.”

Emily Ladau @emilyladau

“Every time I go through security, I am essentially turned into a bit of a sideshow. And then I’ll go through this invasive pat-down process with everybody watching. When they get ready to board, they say, ‘first we have to get the wheelchair on,’ as if I’m not actually a person. I’m just this big piece of inconvenient machinery that they have to get on the plane,” says Emily Ladau in a Youtube video with VICE News. “I never feel quite so much like a burden as I do when I’m getting on an airplane. But even worse than all that’s required to get on the plane can be what happens after landing.” During the flight Ladau’s joystick was damaged and was unattached to the chair when she got it back. “My chair is still not fixed, and it’s been more than a month. I have been driving around with a broken wheelchair held together with duct tape and tire wraps for a month. There is no other method of transportation where I am asked to give up my wheelchair. “

Whether I am on a bus or a train or in my car, I am always with my wheelchair,” she says.

The Human Cost

Nothing illustrates the true risks that wheelchair users face every time they fly like the deaths of Gaby Assouline and Engracia Figueroa. Assouline, already a wheelchair user due to an extremely rare condition, was paralyzed in February 2022 when she hit a junction on a Southwest Airlines jet bridge, causing her wheelchair to flip. She sustained a cervical-level injury and never left the hospital until her death on Jan. 22, 2023. Figueroa’s death on Oct. 31 followed a pressure sore and other related issues after her custom power wheelchair was destroyed by United Airlines on a flight home to California after she spoke at a rally in Washington, D.C.

The story of Nathaniel “NJ” Foster, a vent-dependent quad from New Jersey, has not received as much coverage. Foster was a 21-year-old college student in 2019 when he went into cardiac arrest after being improperly deplaned in an aisle chair. He went into a vegetative state and remains unable to communicate today. The Fosters allege that staff “aggressively pushed” Nathaniel, making it difficult for him to breathe, ignored him saying, “I can’t breathe,” and recklessly disregarded an opportunity to have an available physician assist.

Nathaniel Foster, et al. v. United Airlines Inc., et al., was set to go to trial in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California when this story went to press. On his WheelchairTravel.org blog, Morris describes Foster’s lawsuit as potentially pivotal, calling it “an important test case concerning the limits of an airline’s liability for injuries caused to passengers with disabilities.”

Adding insult to all the injuries and damage is the fact that DOT has levied zero fines on carriers since the reporting on damaged devices began. The 2018 FAA bill tripled the previous maximum fine of $40,000 per instance of damaged mobility aid. With 36,000 damaged devices at $120,000 each, that’s over $4 billion in unlevied fines that might have helped incentivize change. “Without accountability, you don’t have that change in behavior,” says United Spinal Association’s Director of Advocacy and Policy Steve Lieberman.

Still, the mounting bad press from obvious negligence — mixed with story after story of flight cancellations and other recent operational failures — had the industry in need of something positive to shift the narrative and public opinion. A Delta Air Lines subsidiary’s June announcement of the Air4All, a prototype seating arrangement that allows wheelchair users to fly while in their personal chairs, did just that (see Seating Solutions in Progress).

A Better Alternative

Michele Erwin has been leading the fight to allow wheelchair users to fly in their own chairs since she founded All Wheels Up in 2011. After years of raising awareness and funds to show that wheelchair users could safely fly in their chairs, AWU collaborated on the first independent crash testing of wheelchair restraints in 2016.

When the restraints held up, AWU reached out to airline and airplane manufacturer representatives, but Erwin and her team were largely stonewalled. “Nobody wanted to touch All Wheels Up with a 10-foot pole,” she says. The all-volunteer organization continued to fight an uphill battle until the Transportation Research Board mentioned its work in a 2021 report on the feasibility of wheelchair-securement systems inside passenger aircraft. The report had a legitimizing effect that started opening doors. “This was no longer ‘some crazy mom who has an idea,’” says Erwin. “This was a respectable and viable project.”

Their most recent working group, held at Seattle’s historic The Museum of Flight in September 2022, brought together more than 100 stakeholders from 33 different organizations around the globe. “The interesting takeaway was that people who had not been working with us couldn’t believe the incredible progress being made in this space,” she says.

One of those wowed attendees was Buckland, who was appointed disability policy advisor to the secretary of transportation in 2021 after a career running the Idaho Centers for Independent Living and then the National Council on Independent Living. “They have found their niche, and are knocking the hell out of it,” he says.

Building on that momentum, AWU held 22 meetings in three days with elected officials earlier this year to help craft the next wave of legislation, while fielding daily emails from equipment and airplane manufacturers, universities and others reaching out for some sort of help. “There is definitely a heightened awareness of the problem, which is terrific,” says Erwin.

Morris credits Erwin and AWU for laying the groundwork for Delta executives to greenlight the development of the prototype showcased in June. “The work that Michele has done over these last years has been tremendously important,” he says.

The Air4All wheelchair securement space was created by a U.K.-based consortium comprising advocacy group Flying Disabled, aviation design company PriestmanGoode, aerospace company SWS Certification Services and wheelchair design company Sunrise Medical. The seat allows flight attendants to quickly convert a regular airline seat into a space for a wheelchair, with retractable tie-downs embedded in the cabin floor.

Over a few weeks, videos of Morris and British TV personality Sophie Morgan, a T8 para, found viral fame, catching the attention of major news outlets and sweeping through the feeds and inboxes of disabled travelers around the globe.

Morris had been vocal about his reservations prior to seeing the seat, but ultimately came away encouraged by what he saw. “Five years ago I said, ‘Hopefully, in my lifetime.’ So, I’m loving how the timeline is contracting.”

From Feasibility to Implementation

While the news was met with overwhelming enthusiasm from the majority of the disability community, others with long histories navigating an inaccessible world countered with cautious optimism. As the recently retired director of customer advocacy from Alaska Airlines, Ray Prentice is well-positioned to comment on the prototype’s potential impact. “There is still a lot that has to be done in getting it certified on an airplane and integrated with the variety of power chairs (and) finding enough room in the cabin,” he says. “All things that can be worked out, but … there’s a lot to discuss.”

As an engineer at Boeing and a wheelchair user, Anthony Anderson knows all too well that the path from feasibility to implementation can be a long and meandering one. A T8 para, Anderson started at Boeing in the months after the passage of the ADA, working on designs to help airlines meet new accessibility requirements for lavatories on twin-aisle airplanes. It took three years for the first models with accessible bathrooms to roll off the assembly line, and soon afterward Anderson could only watch as twin-aisle planes were phased out for single-aisle planes with inaccessible bathrooms. Anderson sees a lot of upside to the Air4All prototype, but knows there are plenty of hurdles left to get to an implementable design. “It is really tough to estimate time to certify something new,” he says.

Keep in mind that airplanes are expensive and usually have long service lives. Even if the Air4All system or something similar were certified tomorrow, it would be years before they were widely available. And just because an accessible solution exists, until the government requires airlines to allow flyers to sit in their mobility devices, there’s no guarantee they will undertake the costly endeavor of upgrading.

A study by All Wheels Up found that airlines are spending upwards of $3 million a year on wheelchair repairs and replacements. While that may seem like a lot of money, consider that United Airlines alone made over $48 billion in revenue in 2023. Compared to the cost of building and upgrading an entire fleet, $3 million is pocket change. You can bet airlines will hold out on that endeavor as long as they can.

An Improving Forecast

Thanks to the growing chorus of advocates at home and abroad, key decision-makers finally seem to be paying attention. Sen. Tammy Duckworth was one of a handful of prominent legislators to introduce the Mobility Aids on Board Improve Lives and Empower All Act this June. In addition to requiring DOT to provide more details about the damage that airlines are doing to wheelchairs and scooters, the MOBILE Act could lead to an economic impact study finally revealing the true cost of sacrificing some seating and space to allow wheelchair users to sit in their chairs on board. Advocates like Erwin hope its provisions get rolled into the 2023 FAA Reauthorization Act. “We are going to put true economics on this,” she says. “Because, first of all, they have to stop telling you every single flight is full. Give us numbers.”

As the secretary of transportation, Pete Buttigieg would be the person responsible for implementing those requirements. Buttigieg has emerged as a vocal ally for making air travel more accessible. He attended a meeting with disability rights leaders convened by Vice President Kamala Harris to discuss transportation accessibility at the White House in July. He told the attendees that DOT has “begun laying the preliminary groundwork for a rule that will make it possible for passengers to stay in their own wheelchairs when they fly, affording them the same dignity that so many Americans count on in other forms of transportation.”

Days later, on the 33rd anniversary of the ADA, Buttigieg announced a new rule requiring airlines to make lavatories on new single-aisle aircraft large enough to permit a passenger with a disability and attendant (see sidebar below). “We are proud to announce this rule that will make airplane bathrooms larger and more accessible, ensuring travelers in wheelchairs are afforded the same access and dignity as the rest of the traveling public,” said Buttigieg.

From boarding to bathrooms, there are plenty of other issues that matter to people with mobility disabilities, beyond being able to remain in their mobility devices. But Prentice and other insiders I spoke with pointed to Air4All as evidence that the accessibility discussion may have turned a corner. “This shows how one major obstacle was already overcome when smart people get the go-ahead to solve issues,” Prentice says. Anderson urges patience. “Yes, it’s taking forever,” he says. “But when you’re making a huge paradigm shift in thinking and design, unfortunately it takes time.”

The sense that things are changing and a window for real reform may be opening is part of the reason the 70-year-old Buckland signed on as a DOT advisor, with a key factor being the recent $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill that has made massive financial commitments to updating and overhauling the country’s airports, roads, bridges and rails. “We have an opportunity right now to make a once in a generation difference in the built environment,” says Buckland.

As a high-level quad who flies on a regular basis, it’s disheartening to be asked for more patience when our rights continue to be violated and our lives are at stake. And though little seems to have changed for current flyers, what has changed is the groundswell of voices pushing to bring down one of the last major walls of exclusion from equal access to modern mass transportation since the ADA was passed 33 years ago.

What I have come to learn over the past six years of studying the disability rights movement is that true progress is a product of successive waves of activism that incrementally alter the landscape of society over time. Progress will come so long as we all stay engaged and sustain our momentum.

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

This is a fantastic article on the issues of people with disabilities and flying. As a person born with cerebral palsy, I relate to driving thousands of miles to avoid flying. My experiences have been not so bad to terrible depending on the airline and the personnel. Some attendants are terrible and some are accommodating. But more than once I have had to connect to the higher ups in the airline to deal with a wheelchair situation. Nice piece of journalism by Mr. Salvini.

I spend most of my waking moments trying to get out of my wheelchair. The last thing I want to do, is stay in it while flying. No thanks.

Air traveling while remaining seated on our personal custom mobility equipment will finally allow us to safely, comfortably, without trepidation, and with dignity.

The last time I flew, they “lost” my wheelchair, my wheelchair was too wide to fit down the center aisle and even though I had called them numerous times before my flight to make sure they would be able to accommodate me, when I showed up the staff on the airplane said they never knew of any devise to help me. Never again.

I get injured– usually in minor ways– most every time I fly. And I fly quite a bit because my job requires it. But, the worst is when my wheelchair gets damaged. Twice, I have had wheelchairs damaged beyond simple repair, taking months to be repaired.