Editor’s Note: It is hard to believe that Barry Corbet, New Mobility’s editor from 1991 to 2000, passed away nine years ago. So much of what he stood for still influences the content and style of these pages, as well as countless lives. The following narrative is excerpted (and lightly edited) from an article first published in the July 2013 issue of Dartmouth’s alumni magazine. It is an authoritative account of Corbet’s life from his legendary ascent of Mount Everest to the day he became paralyzed and went on to establish himself as an unforgettable pioneer in the disability community.

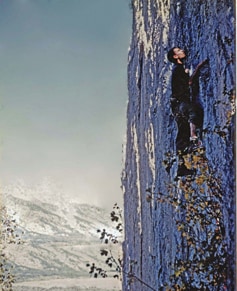

In the summer of 1955, two young climbers from the Pacific Northwest rested at an alpine oasis below the Grand Teton, in Wyoming. Barry Corbet and Jake Breitenbach were in the prime of youth, able to jog uphill while wearing a loaded pack. Corbet was solid and angular, yet gentle and graceful. Breitenbach was all sinewy muscle.

A few days earlier, they had navigated Corbet’s battered 1948 Hudson to the Tetons from New Hampshire’s Dartmouth College. Over an industrious week they climbed six of the Tetons’ highest and most difficult peaks. Initially, they followed piton chips in the rock left by a young student named Jack Durrance, who founded the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club in 1936. Then they broke out on their own, and established several new routes in the range. The Tetons soon became the Dartmouth climbing clan’s untamed, vertical playpen — a proving ground for the skills honed on the primordial rocks of New England.

Corbet was their ad hoc leader. An astute geology student, he reputedly had the highest IQ, at that time, of any incoming Dartmouth freshman. “Barry could do whatever he put his mind to,” said his roommate Frank Sands. One summer, Corbet, Breitenbach and Pete Sinclair decided to take a detour via Alaska, and they forged a new route up the South Face of Mount McKinley. When TIME Magazine asked them why they climbed mountains, they responded, “To get away from tidal waves.”

Not surprisingly, Corbet was selected for America’s first official team to attempt Mount Everest. But Corbet’s buddy Breitenbach wouldn’t make it through the second day of climbing. In the treacherous Khumbu Icefall, he was buried beneath tons of ice when a section of the glacier collapsed on top of him.

The expedition forged on. Corbet chose to join Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein on a daring attempt of Everest’s unclimbed West Ridge. But limited supply of oxygen restricted the West Ridge summit team to only two climbers. Corbet had ferried loads to high altitudes for more than a month, yet he insisted that Hornbein and Unsoeld should go.

“You two have been climbing together, you know each other, and you’ll make the strongest team. What’s more,” he said semi-seriously, “you’re both just about over the hump. This is my first Himalayan expedition; I’ll be coming back.”

To fix their high camp, at 27,225 feet, Hornbein and Unsoeld followed steps that Corbet had chopped with an ice axe up an avalanche-prone chute now known as the Hornbein Couloir. Hornbein and Unsoeld, aided by Corbet’s self-sacrificing assist, would reach the summit on May 22, 1963, in what is still hailed as one of the greatest feats in Himalayan mountaineering.

The Moebius Flip

In the late 1950s, a recruiter for a men’s modeling agency had stopped Corbet on the street in New York City. Riveted by his boyish but rugged features, the recruiter scribbled down the climber’s contact information.

While Corbet was on Everest, a representative of Philip Morris called and spoke with his wife, Muffy. The company had heard about the expedition, and asked if Corbet might consider modeling for a Camel ad. Corbet was a smoker, and when he returned to Wyoming he accepted. He appeared on the back covers of national magazines in a composite photo featuring a well-tanned, virile outdoorsman framed by Everest’s West Ridge. A sling across his chest is threaded with carabiners, glacier goggles are pushed onto his forehead, and one hand holds a pair of leather work gloves. His gaze seems focused beyond the horizon.

In truth, after Everest, Corbet’s gaze had turned inward. A feeling of emptiness and despondency had swept over him after losing his best buddy, Breitenbach. And after an informal, congratulatory parade in Corbet’s honor through Jackson Hole, he and his wife had separated.

Corbet’s friends described him as distraught. To distract himself, he climbed in the Tetons with friends — but he made some careless, dangerous moves as he struggled half-heartedly to pay attention. At one point a large rucksack being hauled up the cliff above him came untied and tumbled past him down the mountain. Corbet barely glanced at it.

But he soon regained his focus and his mountain legs, and over the six years following Everest, Corbet went on to do first ascents of Mount Vinson and Mount Tyree, Antarctica’s highest and second highest peaks.

Filmmaking also provided a lift. Corbet had made some simple movies, and high on the West Ridge he’d shot some footage that showed imagination and technical competence. In Aspen, Colo., he partnered with Dartmouth classmate and adventure filmmaker Roger Brown, who saw in Corbet a brilliant cinematographer and editor. It was a heady time, as they witnessed the birth of stunt skiing and new equipment designs that were quickly changing the sport. With borrowed money, they produced films titled Yoo Hoo, I’m a Bird (for an airline company), Ski the Outer Limits, and The Moebius Flip. Enough income rolled in so that they could hire Norman Dyhrenfurth — the leader of the ’63 expedition, also an accomplished filmmaker.

It was while working with Dyhrenfurth that Corbet’s life was abruptly transformed. On a mountain near Aspen, the helicopter from which Dyhrenfurth and Corbet were shooting landed briefly. Two Bonne Belle girls — models wearing tight, padded one-piece suits and stylish buckle ski boots — were dropped off, and prepared to launch into a synchronized skiing routine when the cameras rolled. Corbet had been shooting from the ground all day, and was cold from standing in one place. Dyhrenfurth suggested they swap places, so that Corbet could shoot aerials. Corbet climbed into the chopper.

Unaware of the risk, the pilot had lashed two boards cross-wise onto the whirlybird’s skids, to improve buoyancy when landing in soft snow. The helicopter skimmed only a few feet off the snow, following the skiers, while Corbet filmed. But sunlight filtering through a high haze offered little depth perception on the smooth, powder snow.

The boards lashed to the skids suddenly snagged on a bump, tripping the chopper. It slammed into the slope, and — in an apocalypse of tearing metal and flying debris — tore apart as it flipped upside down. Corbet was thrown through the Plexiglas bubble.

The snowy landscape went silent. Dyhrenfurth was stunned. He scrambled down from his filming perch and saw Corbet’s nose emerging through the snow. The pilot was hanging upside down, unhurt. Dyhrenfurth struggled to keep Corbet alive.

The Bonne Belle girls rallied into action. They yanked the door from the helicopter, fashioned it into a snow toboggan, and transported Corbet to level terrain. Then the ski models raced down the mountain to find help.

“I recall praying to God,” Dyhrenfurth said, “something I had never done before.” Another helicopter landed and evacuated the pilot and Corbet — who was unconscious — to Aspen Hospital. Dyhrenfurth was left shivering in the cold and darkness for hours — feeling more isolated than he ever had on Everest — until another helicopter retrieved him. The pilot survived — though he would be killed several months later in another crash.

Roger Brown — who’d originally been scheduled to shoot that day in place of Corbet — drove up from Vail. Corbet’s eyes were open, but he couldn’t recognize Brown. His injuries were clearly life-threatening, and he was evacuated to University Hospital in Denver, where he endured eight hours of abdominal surgery. After that, the doctors examined his spine.

The prognosis was dire. Corbet would live, but his spinal cord had been damaged. He would be permanently paralyzed from the waist down. He was 31 years old.

Some Serious Adjustments

Two months after the helicopter crash, Corbet rolled his wheelchair out of the hospital and moved into an apartment on Denver’s Colorado Boulevard.

“I didn’t know a single paraplegic. In 1968, nobody told people like us that we might live a normal life span. So it was easy to buy into the prevailing dictum to live fast, die young and leave a beautiful memory. I took that as a license to party hardy, and I did,” said Corbet

Like many of his friends, Corbet had a healthy taste for booze. Now he really had something to drink about. Some of his old friends were reticent to visit, simply because they didn’t want to see him disabled. They remembered Corbet as an “SAB” — supremely-able-bodied — and they wanted to cherish that image. Corbet himself didn’t mind the solitude. He needed some time alone to figure out how to live independently — assuming he could live at all. His ex-wife, Muffy, continued to visit, and he asked her to bring his crutches, hopeful he would someday be able to use them.

Gradually, his friends began to reappear. “I saw him at the apartment,” said David Peterson, a climber and doctor from the Tetons. “The room was dark, and his attitude was dark. He was searching, beseeching, grasping at any hope for a cure — acupuncture, acupressure, faith healing, neurosurgery — anything.” Corbet had even explored a “Philippine Miracle Healing Rescue,” in which a medical practitioner magically “reaches into” the person’s abdominal cavity with his hands to extract tumors and other obstructions. Peterson was dubious. “I could only say, ‘Barry, I love you — but there’s nothing I know of in medicine that we can offer you. The best thing for you is to get into rehab.’”

Corbet had told friends of feeling depressed even before his accident, when he didn’t know where his life was heading. He had also developed emboli in his legs from inactivity when he was nearly comatose in the hospital. These clots had broken away and lodged in his lungs — a dangerous occurrence at that time. As if these afflictions weren’t enough, inner demons — far more tenacious and frightful than anything a mountain had unleashed on him — began to appear. Breitenbach’s death may have given the demons space to roam.

The only way out of his gloom, Corbet decided, was to reclaim his athletic, outdoor life by any means possible. University Hospital, however, hadn’t provided him with physical therapy; he had little idea of where the boundaries lay for people with disabilities. Denver’s Craig Hospital, nearby, was emerging as a leader in therapies designed to re-integrate disabled people into active, productive lives. A long-time staffer described Craig as “a cross between an elite neurological institute, college campus, fraternity house and boot camp.”

Corbet came on board. He jumped into every activity and sport he could imagine, and set out to become “the most active gimp who ever lived.” His anything-is-possible, go-for-it spirit infected Craig’s other residents. He perfected what he called “ballistic transfers,” in which he would move from a wheelchair to a car or bed in a single explosive, yet fluid motion. He exceeded the range of movement that the staff had imagined possible. This was a guy who had climbed on Mount Everest, after all.

Corbet’s creative spirit couldn’t be restrained, and soon he jumped back into adventure filmmaking with Roger Brown. While shooting footage of kayakers from a raft on the Colorado River, at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, Corbet observed something that switched on a light bulb: The skill and maneuverability of the kayakers paddling around him depended primarily on the use of their arms.

In 1976, virtually no paraplegics had ever kayaked. Ben Harding, a studious-looking water resources engineer, and Link Hibbard, a women’s national whitewater champion, had been teaching amputees to kayak. But until they met Corbet, they’d never considered it something paraplegics could do. Now, once a week in Boulder, they met with Corbet at the University of Colorado swimming pool for lessons on how to “Eskimo roll.” When kayaking on a river, Corbet would have to be able to roll, since ejecting himself from the kayak would be difficult and risky, with no help from his paralyzed legs.

“As far as I know, he was the first paraplegic to do a successful roll,” Harding said, “though learning this wasn’t easy.” To begin with, Harding and Hibbard had to secure Corbet in the cockpit with a wedge of polyurethane foam between his legs.

The staff at Craig Hospital didn’t approve, knowing skin injuries can be perilous. On one river outing in early May, Corbet flipped his kayak in freezing water and tried unsuccessfully to roll it up. He was forced to exit the boat. This entailed yanking the cord that held the spray skirt, ejecting the piece of foam across his lap, then wrenching his torso and paralyzed legs out — all while underwater, upside down, and moving swiftly downriver amid boulders and obstacles. Gasping for air, he was able to work his way close enough to shore to be out of immediate danger.

Kayaking had given him not only a new means of mobility, but a new skill to master. Using ropes and pulleys, he constructed a device in his garage for loading kayaks onto his modified van. The governor of Colorado granted him special dispensation to secure the kayaks on the side of his van, normally illegal. When pulled over by state troopers, Corbet would withdraw the governor’s letter from the glove box.

“When I first met Barry, he was one pissed-off guy,” Harding recalled. “He had been the best at two things — climbing and skiing — and now he wanted to be the best ‘crip kayaker.’ Maybe paddling appealed to him because, while sitting in a plastic boat, he could be like everyone else.”

Corbet had become “Super Crip,” a new breed of radicalized hero. “Super Crip leaps curbs in a single bound,” Corbet later wrote, describing how some wheelchair-using youth careen around cities and suburbs with a combination of finesse and unruly abandon. “Always a bang, never a whimper, independent to a fault. Super Crip needs little, and asks for less — the living proof that people with disabilities need no accommodation.”

Consistent with that approach, Corbet resisted doing anything with other disabled people. He had been paddling mainly with nondisabled kayaking buddies. Then, Link Hibbard asked him to join up with a group of other disabled boaters. Corbet was surprised by how quickly they adapted to the outdoors, the water, and their bodies. As he tested himself, he cajoled his new kayaking buddies to take on rivers of increasing intensity. Gradually, he learned there were no stars or heroes in this game — only friends, colleagues and fellow experimenters. It reminded him of the team spirit that had slowly taken hold on Everest when the members realized that, to reach their individual goals, they truly needed each other.

When the Everest team gathered for reunions, he felt a mild sense of disconnection. Although most of the members had gone on to successful careers in other realms, some of them seemed to cling to that historic time period, to attach their identity to their achievements. Though he didn’t express it to the team, he felt he had touched something even larger than Everest, more substantial than the pursuit of personal excellence. He had discovered the longer-lasting sustenance of a community of friends and family, and the magic of living in the present moment.

Warriors on Wheels

For awhile, Corbet succeeded as a Super Crip. But he wore out the rotator cuffs in his shoulders and began to lose the use of his arms — which he found more debilitating and frustrating than paralysis of his legs. “He recognized that upper body strength, guts, determination, and intellect could no longer compensate for his paralyzed lower limbs,” said Roger Brown. “He might outwit the river, but he could no longer overpower it.”

In effect, Corbet was devolving from a paraplegic into a quadriplegic. “I’m running out of limbs,” he said. Then post-phlebitic syndrome, which causes swelling in the extremities, led to the amputation of his toes. His feet were literally following the footprints of Willi Unsoeld’s frostbitten toeless feet, post-Everest.

After his daughter Jennifer left for college in 1983, Corbet faced an empty nest. His sons, Jonathan and Mike, were already on their own. Darkness again gathered around him.

Advocating for disabled causes brought him partial relief, and a new sense of direction. “In the 1960s, we had no idea that the civil rights rhetoric had anything to do with us,” Corbet said. “Disability rights? Never heard of ’em. What would we do with them?” But by 1968, the year of his accident, people were beginning to view disability differently. Higher education for disabled students was already proving to be a good idea. In 1968 the Architectural Barriers Act required that government-funded buildings be made wheelchair accessible. The Americans with Disabilities Act was still two decades away, but wheelchair activists had rolled out of the starting gate and were gathering momentum.

Corbet saw that people with disabilities were isolated both geographically and socially. Until the Internet came along, they were also politically fragmented — not speaking with a single voice, and rarely gathered in a single place. “Disabled children usually aren’t born to disabled parents,” Corbet pointed out, “so we don’t have family transmission of values.”

He worked on exposing the absurdities of Medicare rules that literally imprisoned disabled people in their homes: If officials learned they were active and mobile, the home care assistance they needed might be withdrawn. And, though Medicare covered months of hospital care, it didn’t cover custom-shaped orthotic seats for wheelchairs — the very items that could prevent the need to spend months in the hospital. Changes — an artistic documentary shot about people in wheelchairs, which Corbet filmed in the early 1970s from a wheelchair — profiled wheelchair users in Craig Hospital rehab as they re-built productive lives.

Corbet no longer wanted to be characterized as a climber. It was a frame of reference that could only exist in the past. “Sure, climbing a peak has mythic connotations,” he wrote, “but so does boarding the subway. These days I attach more importance to getting into public buildings or onto buses — both of which can be ultimate challenges for someone in my position.”

At the same time, Corbet felt that some disability rights activists had become too politicized. “There’s much to do besides being disabled,” he reiterated, noting a tendency among disability advocates to blame everything that’s not right with their lives on discrimination. He campaigned, for instance, that the wilderness not be made wheelchair accessible. “The thought that wilderness exists is enough. I don’t need to be in it. Make the bathrooms accessible — but leave the mountains alone.” When counseling those coming into Craig Hospital, he urged them to find the middle ground between warrior-like Super Crip and heart-wrenching poster child, between admiration and pity.

Emergence of New Mobility

In late 1991, Sam Maddox, farsighted founder of a much-needed resource for people with spinal cord injuries — Spinal Network Extra — handed the reins to Corbet, and the magazine was renamed New Mobility. It had a strong reputation as a fearless service title, a place where people with SCI discussed taboo topics like sex, fertility and other altered bodily functions. Corbet, at 55, injected it with heart and with guts and the unmistakable voice of personal experience. His irreverent, intelligent writing — including articles titled “Handicapitalism” and “Freak Love” — set a tone that anchors the magazine today.

His brotherly gang of irrepressible, disabled kayakers helped inspire his provocative point of view: It wasn’t about what sort of late model wheelchair or orthopedic mattress you had. It was about who you were and how you approached life. Corbet recognized that there was “power in lifestyle.” One reader of New Mobility wrote to Corbet that she had been disabled since age 8, but was 19 years old before she encountered a “crip” magazine. “It was intoxicating,” she said. “Even the catheter ads were liberating. I had no idea that disability was discussed outside the hospital.” She’d discovered the community that Corbet had helped create: like-minded people who were reinventing themselves from the ground up.

“Collectively, we can speak the unspeakable,” Corbet said, summarizing his mission with the magazine. “It’s really defeating if you think you’re the only person on earth who does that to breathe, or does that to empty your bladder, or does that to make love. When we speak the unspeakable, we can get over our bodies — our poor, banged-up bodies.”

Corbet studied Tibetan Buddhism and practiced meditation, which led him to see the world as it was, not as he hoped it would be. “Until I became a paraplegic,” he said, “I never had a sense of who I was and what I was doing. The injury forced me to face up to everything.”

The Buddhists say that we are blessed, or doomed, to live many lives. The disabled often refer to two lives: before the accident, and after. “All of us,” he expressed, invoking the “severely-able-bodied” moniker, “should accurately be described as TABs, or ‘temporarily-able-bodied.’ Everyone will be disabled at some point — it’s just a matter of time.”

Sunrise Beyond the Mountains

Corbet’s perspective had evolved over years of pain and reflection. In the early 1990s, he drove with his children through Jackson Hole for the first time since his accident. At a turnout overlooking the Snake River, the most majestic peaks of the Tetons — the Cathedral Group — rose above the far bank like a shrine to his former life. His second, disabled life confronted the immutable icons of his first life as he silently traced the routes he’d so often climbed and guided. For two hours he sat in silence, trying to knit together the chapters of his life.

Later, Corbet regretted dividing his life. “With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to see that there is no first life, no second life. There’s this life, and it’s everything we ever hoped for. It’s the brass ring we thought we had missed. Life is complete and terrifying and drop-dead gorgeous, and I have just as big a piece of it as anyone else. We get the whole ball of wax, with or without a disability. Like it or not, we are stalked by our everyday adventures, our ordinary conquests. Teach us to embrace them, to value them. Teach us that there’s no escaping the greatest adventure of them all — being part and parcel of the solar wind and the play of starlight, of the pull of tides and the convergence of hearts — this luminous life that is denied to no one. Not even gimps.”

Family was one of those everyday adventures. “When my son was born,” daughter Jennifer said, “I handed him to my father and said, ‘James Barry — meet James Barry.’ He burst into tears.”

Corbet’s namesake grew up tooling around the patio in his plastic roller-chair, playing bumper cars with his grandfather’s wheelchair. Meanwhile Corbet’s granddaughter would lunge, giggling, for the toggle switch on Corbet’s electric wheelchair, making him carom off in wild directions. He had regarded his children, when they were young, as a liability to his adventurous lifestyle. Now they — and their children — had become the true loves of his life.

Corbet had completed a metamorphosis. He had transitioned from being a physical and intellectual being into a spiritual being. To whatever degree his disability played a role in that, it was a gift. He would need that gift in the days remaining to him. In 2004, doctors diagnosed Corbet with inoperable, metastatic bladder cancer. He declined chemotherapy. The side effects, including even more loss of mobility, could not justify a marginal increase in longevity.

Corbet had long thought about mortality, and written on the subject in New Mobility. He opted to discontinue consuming food and fluids. Fasting can be a simple and relatively painless way to maintain control over the timing of the inevitable — and to better assure a sense of mental coherence at the moment of death, a skill of key importance to Buddhists.

Muffy, Jennifer, and the Corbet family gathered.

“We felt privileged that he was sustaining us when you might expect just the reverse,” said Muffy’s brother, Roberts French. “He showed extraordinary calm, even joy and radiance — while we were feeling terrible.”

Corbet had stopped taking fluids and food. On December 10, he invited Tom Hornbein to join the family at his ridge-top home. Hornbein booked a flight to Denver and arrived that evening. He was enfolded into Corbet’s extended family.

After three days of fasting, Corbet’s hunger diminished. He didn’t appear to be in pain, but felt some nausea. His lips tended to dry out, and Hornbein and the family moistened his mouth with glycerine. Hornbein spoke with him about Buddhism and read poetry, which had a canny way of drifting toward themes of death. One evening, Hornbein read aloud from Winnie-the-Pooh. The family first lingered in the doorway, then quietly circled around, captured by the lyrical notes of a soft and pleasant world. The Hundred Acre Wood where Winnie-the-Pooh and Christopher Robin lived was a perfectly imperfect community, a refuge composed of natural, unchanging beauty and unbreakable bonds of fellowship. Corbet had already lived there — in the disabled world, as well as on Mount Everest.

Corbet was ready. At 68, he had no regrets, and no complaints. The prospect of departure appeared more comfortable to him than for those around him.

The morning of December 18th — the 38th anniversary of his first ascent (with 10 others) of Antarctica’s Mount Vinson — Corbet was awake, and spoke a few words. At his side sat Paco, the “Yellow Dog,” a chow mix from the pound who had served as his muse for his editorials in New Mobility. As the afternoon arrived, his breathing became more ragged, and he became increasingly drowsy.

“If you’re hanging on for something,” Jennifer whispered to her father, “don’t hang on for us.”

Hornbein sat at Corbet’s bedside. “With his family and other loved ones tied into the metaphorical rope, a climber one time more, he started up that final pitch,” Hornbein wrote. Corbet was again leading the way, just as he had when he’d cut steps in the ice for Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld up the Hornbein Couloir, en route to Camp 5 West on Everest.

His breathing stopped. Hornbein took his hand. “You made it, Barry. You made it,” Hornbein said quietly.

Hundreds of family and friends attended the memorial service, not far from the ridge-top house. Among them were two distinct groups: climber-adventurers, and friends and associates from his New Mobility family. Many in wheelchairs had little idea that Corbet had once been a legendary climber. The climbers were largely unaware that Corbet had become a beloved spokesman and unofficial poet laureate for people with disabilities.

Barry Corbet had led two lives, after all. He was a guide in both.

A Final Award

A year before Corbet’s death, his daughter Jennifer had begun to hear rumors about her father’s recruitment — along with Dartmouth Everesters Barry Bishop, Dave Dingman and Barry Prather — for a clandestine expedition to Nanda Devi, a peak in northern India. From 1965 to ’68 the CIA assigned these climbers, and a cast of Sherpas, to place a plutonium-powered surveillance device high on the peak — hoping to spy across the expanse of western Tibet to where the “Red Chinese” were undertaking nuclear missile tests.

Jennifer learned that, at the end of the operation, Corbet had been presented a medal in a private ceremony in Washington, D.C. A moment later, in a scene that calls to mind Catch-22, the medal was taken away from him.

“You’re not allowed to keep the medal or talk about it,” the case officer informed him. There was no official acknowledgment that it had even been awarded.

Now, 36 years later, she wanted to see if she could get the medal back.

“Have you ever tried calling the CIA?” she asked. “You can’t. Their website doesn’t list phone numbers. If you do find a working number, every line leads you to recorded messages that don’t have voicemail boxes.”

Jennifer, now a tall, self-confident young mother, called the office of Colorado Sen. Tom Tancredo. One of Tancredo’s staffers contacted the Agency. Before long, Jennifer received a call from a man who sounded severe, yet vague. He gave no hint of who he was, or what he was calling about.

“I’m fairly straightforward,” Jennifer said. “So I simply asked him: ‘Is this the CIA?’”

It was. A date was set up for an official medal presentation. In late 2003, a knock was heard on the door of Corbet’s house. The visitor, a sweet-faced man in his 30s, identified himself as a CIA case officer.

Advising the gathered family that he was “still under cover,” the case officer began the ceremony. With reverence and solemnity — the officer was clearly honored to be in Corbet’s presence — he recited a tribute recognizing James Barry Corbet for service to his country. He then presented Corbet with a certificate, a pin, and the medal itself: the CIA’s coveted Intelligence Star, awarded for actions of “extraordinary heroism.”

Support New MobilityWait! Before you wander off to other parts of the internet, please consider supporting New Mobility. For more than three decades, New Mobility has published groundbreaking content for active wheelchair users. We share practical advice from wheelchair users across the country, review life-changing technology and demand equity in healthcare, travel and all facets of life. But none of this is cheap, easy or profitable. Your support helps us give wheelchair users the resources to build a fulfilling life. |

Recent Comments

Bill on LapStacker Relaunches Wheelchair Carrying System

Phillip Gossett on Functional Fitness: How To Make Your Transfers Easier

Kevin Hoy on TiLite Releases Its First Carbon Fiber Wheelchair